Your cart is currently empty!

The State of Engineering Worthy Performance and the 10 Standards, Part 3

By Tim R. Brock, CPT, Ph.D.

This article was originally published in the April 2020 issue of Performance Improvement.

Abstract

This three-part series began by highlighting an eclectic paradox currently perplexing the HPT profession. The second article offered a solution based on 10 design-thinking principles from the field of innovation. This final article uses a case study to show how these 10 design-thinking principles help the human performance technology (HPT) practitioner overcome the eclectic paradox when applying the 10 standards. It provides a new logic lens that brings greater HPT clarity and meets Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles.

Part 1 of this article ended with a paradox. Part 2 ended with a proposed path forward by returning to Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles to deliver and evaluate worthy performance. Part 1 concluded that human performance technology (HPT) practitioners should advocate what makes this profession unique to attract like-minded professionals from other disciplines to integrate the HPT standards into theirs, because HPT offers something missing from their performance improvement frameworks. It ended with this admonition from Gilbert: “Although eclectic systems may sometimes be useful, they seldom have the simplicity and never the elegance that I have held as criteria for success. But eclectic systems do have one sensible quality that all who offer ideas might envy. They know there is more than one way to look at the world” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 5).

Part 2 explored how the HPT profession can add a new way to look at the world while returning to the elegance and simplicity the profession advocates by integrating design-thinking principles from the world of innovation. It offered a framework that HPT practitioners can use that allows them to integrate a logic chain, with the A2D2IE process, the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement, an HPT model, and principles of design thinking to deliver and evaluate outcomes and results that matter to stakeholders who matter.

Part 3 uses a case study to show how what was covered in Parts 1 and 2 was applied in a real-world performance improvement initiative.

CONTEXT CASE STUDY: ABSENTEEISM REDUCTION PROGRAM

The following case study 1 demonstrates how the business alignment V-model provides an advanced logic process the HPT practitioner can use to apply the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement in a way that is easy to grasp and explain. This case study demonstrates how to apply the first three steps of the design-thinking process. The HPT practitioner applies the first four standard principles along with process standards 5 and 6 and also plans how to implement standards 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10. Practitioners use the product of these first three process steps to design and develop the solution (HPT Standard 9) and then evaluate the program as planned, using Steps 4–8 of the process (HPT Standard 10). These first three steps can occur simultaneously for each of the five needs-objectives- evaluation levels.

A bus transit system at a major U.S. city-operated over 1,000 buses every day, every hour. They employed over

2,900 drivers. They also hired a pool of 231 substitute bus drivers to replace absent bus drivers. When the substitute drivers were assigned to replace an unexpected no-show driver, there were bus delays. When the substitute drivers were not driving for an absent driver, they performed no essential work for the remainder of their shift.

Steps 1 and 3: Start with Why, Align Programs with the Business and Expect Success; Plan for Results

Step 1 is concerned with establishing a needs-driven business case for the performance improvement intervention at Levels 5 and 4. The measures defined at Step 1 provide the baseline “as-is” measures to write the “should-be” program objectives that will define what these stakeholders expect in return for their investment. These level-specific program objectives are used to determine how the organization will evaluate the effectiveness (Av) established by the business measures as well as the efficiency (Aw) established by the return on investment (ROI) of the program. Together, they will determine how well the program did to meet these program objectives that define success. HPT practitioners want to learn what worked, what did not work, and what actions are required to improve the program to achieve the appropriate objectives.

HPT practitioners want to evaluate the program to determine whether the program was designed for success. The first and final ISPI standards require this. HPT practitioners want to collaborate with the appropriate stakeholder to determine how everyone agrees to evaluate the program to learn whether it mattered to the program participants so that they are willing and able to change their workplace behaviors. HPT practitioners collect these data at Step 4 of the design–thinking-for-results process.

HPT practitioners also want to plan how they will collect data to determine whether the desired changes have affected workplace performance outcomes as expected. Workplace changes may include organization performance variables (i.e., Gilbert’s information, instruments, or incentives) or human behavior variables (i.e., Gilbert’s knowledge and skills, capabilities, or motivation) improvements. HPT practitioners collect these data to evaluate during Step 5 of the design-thinking-for-results process. Was what was learned by the participants and changed in the workplace done in a way so that it became a daily practice? If not, why not? Even more, with this improved behavioral performance, did the business measures the program was funded to improve, actually improve. These measures are the organization’s defined valued performance or accomplishments.

Finally, HPT practitioners want to plan, with the appropriate stakeholders, how they will evaluate the impact (or valued-performance measures) of the program. First, HPT practitioners must plan with the stakeholders how they will isolate the Level 4 impact of the program. They must plan how they will answer the question, “How do you know the impact you are claiming is directly related to your program and not something else?” Executives expect HPT practitioners to give credit where credit is due to protect relationships and credibility. There are multiple credible techniques such as control groups, trend-line analysis, mathematical modeling, estimates, and others.2 Furthermore, HPT practitioners must plan how they will collect program costs, decide which impact measures to convert to monetary values or leave as intangibles, and choose how they will report the results of the program’s effectiveness after they evaluate the program against the program’s objectives.

In summary, at Step 3 HPT practitioners are planning for success. They do this by using the five levels of program needs the HPT practitioner aligned at Steps 1 and 2 (i.e., two at the organization-performance level and three at the human-performance level) to write the outcomes and results objectives the program is expected to deliver. They will use these program objectives to evaluate 2the program to determine how well the program did to achieve those objectives.

For this case study, the HPT practitioner collaborated with the appropriate stakeholders to accomplish the three program-planning-process steps. The first step was to define and align the program needs. 3 The second step was to craft the five “should-be” program objectives the program is expected to achieve. The third step was to determine how the HPT practitioner will evaluate each objective. Now the performance improvement team had what was necessary to design, develop, implement, and evaluate the performance improvement intervention that all the key stakeholders agreed to support because they had a voice during the planning phase to make sure that what was planned was feasible, sustainable, and what they want.

In summary, these first three steps help HPT practitioners either apply or plan to apply all 10 HPT standards using a more detailed process that complements the six HPT process standards while integrating the four HPT principle standards at every step. The following case study should add some clarity to how this design thinking for results process works in the real world.

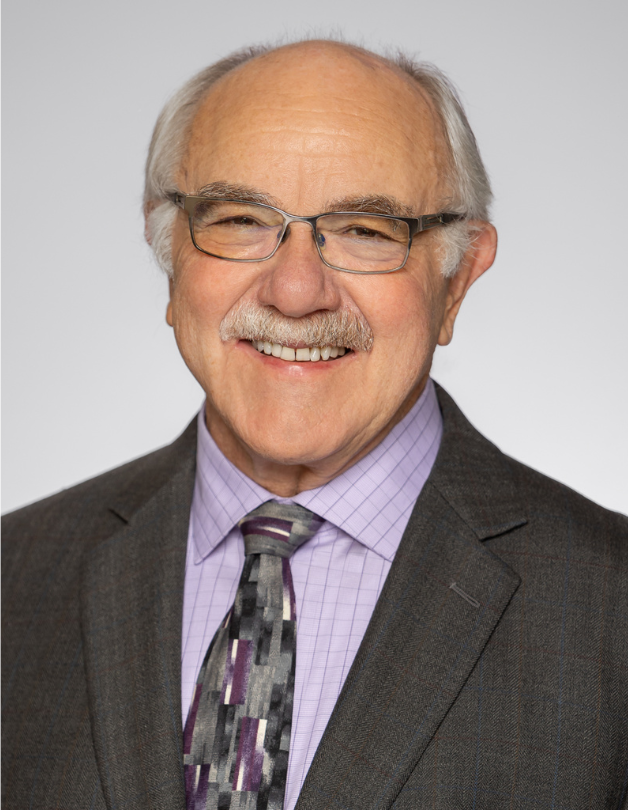

Level 5 payoff need, program objective, and ROI evaluation plan

Executives noted that their driver-absenteeism rate had increased over the past three years and from 7% to 8.7% during the past three months. This rate was reducing their ability to provide consistent and reliable transportation service to their customers due to bus-route schedule delays and bottlenecks. This resulted in escalating customer complaints, a loss in revenue, and higher operating costs. The executives decided that the rising absenteeism trend was a problem worth solving to reduce these avoidable costs and complaints and save the company’s reputation. They also wanted to make sure that the cost of the solution did not exceed the expected amount of increased revenue and costs avoided. They decided they wanted at least a 25% ROI for this intervention. This is good for HPT practitioners to know upfront.

Using the business alignment V-model in a table format, Figure 1 indicates how the first and third steps of the design-thinking-for-results process align the program needs with the program objectives and how they planned to evaluate the program at this worthy-performance level. The second step shifts from an organization-performance perspective to a daily operations (i.e., workplace) human-performance perspective. The A2D2IE phase is included with each process step to cross-reference the advanced logic chain depicted in Figure 1.

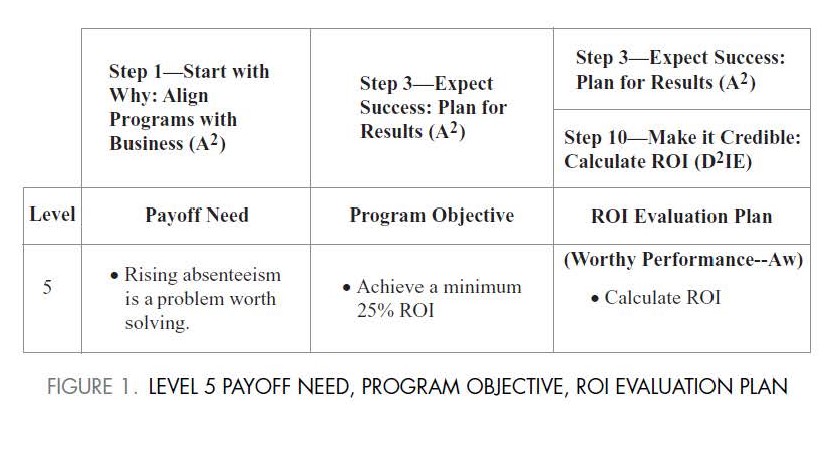

Level 4 business needs, program objectives, and impact evaluation plan

Working with the executives, the HPT practitioners decided to focus on three interrelated business measures:

- Absenteeism rate. Since this was causing internal- revenue and costs problems, focusing on this measure would be the lead indicator for the other two business measures they considered to be lagging

- Job satisfaction. If the drivers reacted negatively to the solution, the solution could make the absenteeism (and turnover) rate

- Customer service. This is their mission. If the intervention fails to address this need, it

Figure 2 shows how they aligned these three organizational business-measure needs with the program objective for each need. It also shows how they planned to evaluate the program at the valued-performance level.

Notice how the Level 4 business needs and objectives are aligned to address the Level 5 payoff need and objective. While the needs and objectives are related to the ROI formula (or Gilbert’s worthy performance formula) numerator (i.e., monetary benefits), the denominator is affected by the performance improvement costs involved in improving these business measures.

According to the integrated-logic model, only Levels 4 and 5 are considered results. Level 4 is the program- effectiveness result that executives value. Level 5 is the financial result that establishes whether the program was efficient and qualified as a financially worthwhile investment.

Another important decision made at this level is how the HPT practitioners will analyze the Level 4 impact measures. The analysis planning requires the same level of stakeholder involvement as Steps 1–5 of the design- thinking-for-results process. At design thinking Step 7, the goal is to make the results-evaluation data credible. First, they decided how they would isolate the effect of this new policy from other factors that might affect the Level 4 measures. It is crucial to answer the question, “How do you know the Level 4 improvements you are claiming are the result of this program and not something else?” HPT practitioners want to give and take credit where credit is due. In partnership with the key stakeholders who can support and approve the action, the HPT practitioners determined which method was most feasible to use for the three Level- 4 measures.

Next, they planned to use salary and benefits to convert isolated absenteeism data to a monetary value. They also decided to leave the employee job-satisfaction and bus-schedule-delay numbers as intangibles (i.e., not converted to monetary value). Finally, they planned with the key stakeholders how they would collect all the costs associated with the A2D2IE process to be able to calculate a credible ROI or worthy-performance result. The monetized, isolated absenteeism value goes in the numerator, and the program costs go in the denominator.

These two levels identify the needs associated with Level 5 payoff worthy performance (Aw) and Level 4 business valued performance (Av). This worthy and valued performance can include societal needs advocated by Kaufman and Guerra-Lopez (2013). These needs- assessment/analysis and alignment actions (HPT Standards 5 and 6) are done in partnership with the stakeholders (HPT Standard 4) to define the results measures that matter to them (HPT Standards 1, 2, and 3). This increases the likelihood that the HPT practitioner will design, develop, and deliver (HPT Standard 7) an acceptable, feasible intervention (HPT Standards 8 and 9). Doing so should produce results the stakeholders value and consider worthy because they are based on the evaluation data that the HPT practitioner collaboratively plans with the stakeholders to improve, measure, evaluate, and report (HPT Standard 10).

Steps 2 and 3: Make It Feasible, Select the Right Solution, and Expect Success; Plan for Results

Once the why question is answered, the second step of the design-thinking process is to figure out what must change in the workplace to allow selecting the most feasible solution(s). It aligns Levels 3, 2, and 1 to ensure the HPT practitioner addresses the needs identified at Levels 4 and 5. The HPT practitioner now moves from the organization- performance needs to human-centric performance needs and is viewing performance in the shoes of the people who must change their behavior to improve their workplace performance to improve the Level-4 business performance measures.

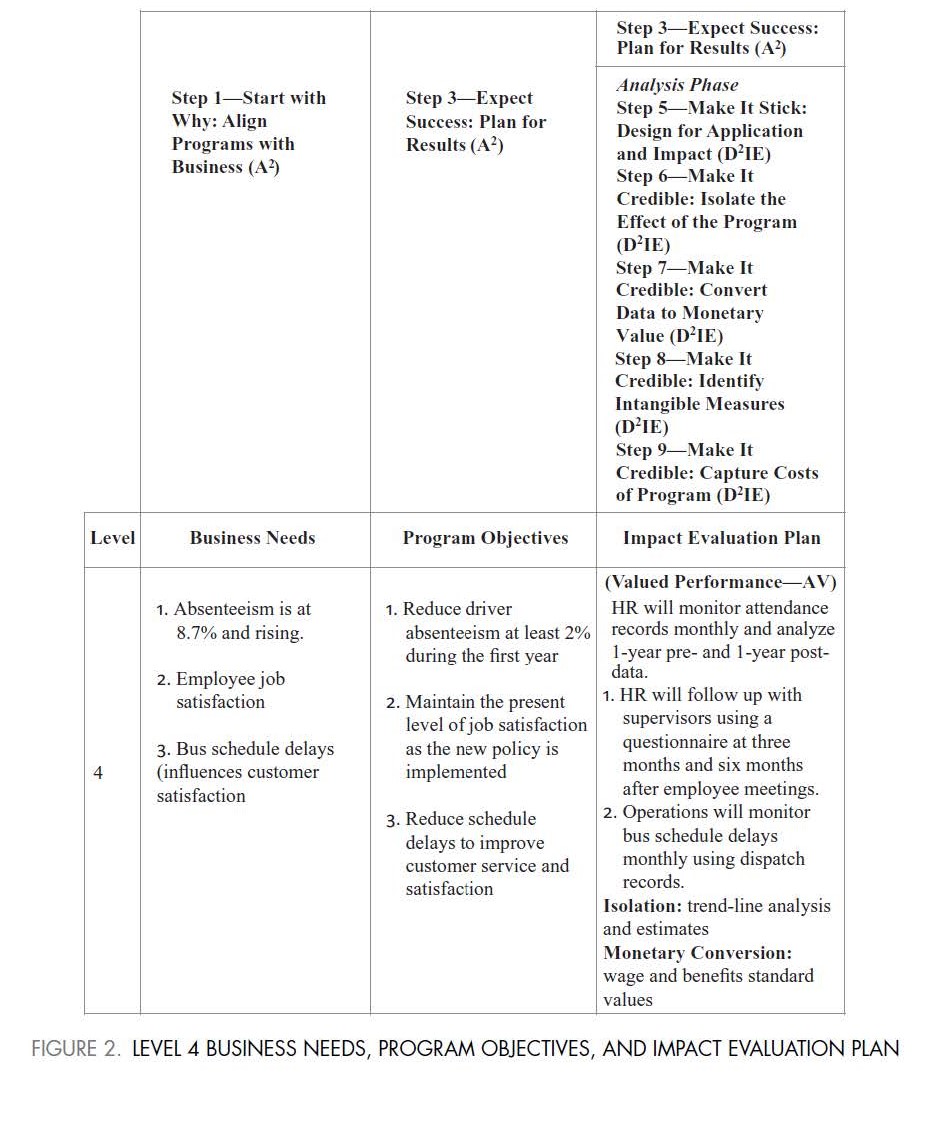

Level 3 performance needs, program objectives, and application-evaluation plan

This is where HPT professionals can excel. For this example, they used focus groups with bus drivers and their supervisors. They also interviewed supervisors and managers. Finally, they analyzed HR records for absenteeism trends and patterns. Here is what they learned:

- Drivers were gaming the system. Their attitude was to take advantage of the system whenever possible. They would step up to the line for getting fired but not step over it.

- This absenteeism problem was avoidable. This problem was primarily driver motivation and a lack of disciplinary measures on the part of the

- Drivers who were habitual no-shows had an absenteeism history dating back to when they were In many cases, this pattern of behavior had also occurred with previous employers.

To address these three root causes, they decided to implement two new processes:

- They created and implemented a no-fault disciplinary system. To satisfy union demands (the union agreed that absenteeism was a problem), the no-fault policy allowed up to five unexpected absences each quarter to accommodate for illness and other unexpected life issues. The sixth unexcused absence, not related to a verifiable, valid personal or family issue, would result in termination.

- They also revised their hiring process to screen out applicants who had an absenteeism history going back to their high school days.

Here is what this looks like using the business- alignment V-model (see Figure 3). Note how vertical and horizontal alignment is taking shape. Every cost associated with improving Level 3 workplace performance and evaluating the program at this level is included in the worthy-performance formula costs to achieve the Level 4 valued performance. Only monetized Level 4 valued performance results belong in the numerator.

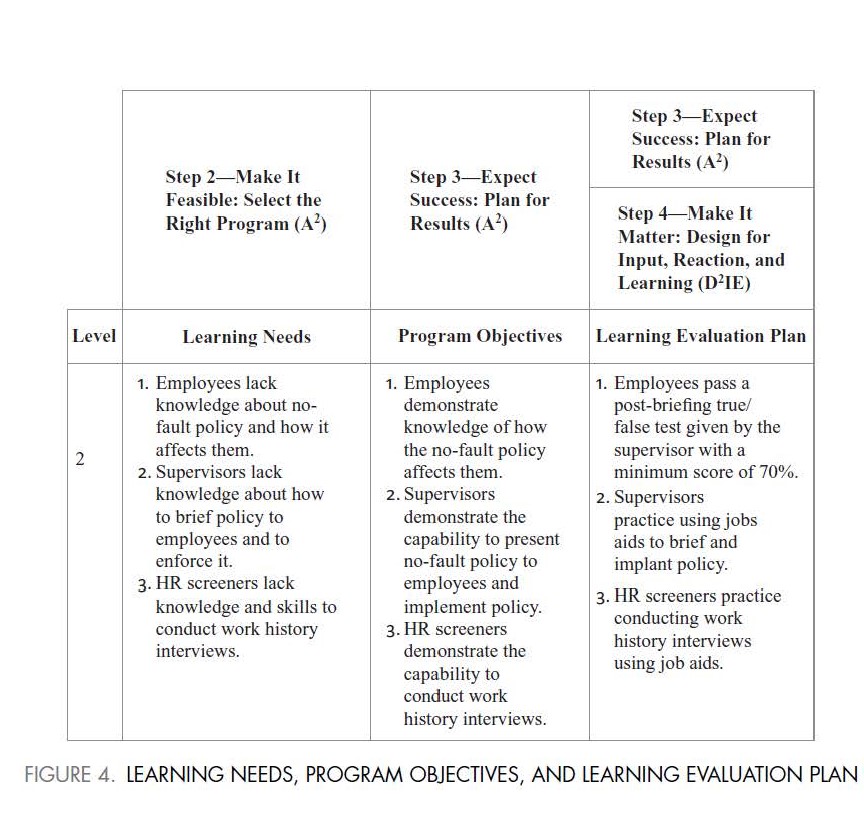

Level 2 learning needs, program objectives, and learning-evaluation plan

All employees had to learn about the new no-fault policy and how it affected them. Employees learned about the new policy from their supervisors during a team meeting. Supervisors had to learn about the new policy, how to brief their direct reports, and how to implement and enforce the policy. All managers had to learn about the new policy and how they were expected to enforce it. HR had to learn how to implement the new screening procedure during the hiring process to ensure new hires did not have a work-attendance-problem history. HR also added the requirements of this no-fault policy to their employee- orientation program.

In the maturing business alignment V-model (see Figure 4), notice how the Level 3 needs drive the Level 2 needs and subsequent objectives and evaluation. This format makes it easy to plan and communicate with stakeholders to comply with the HPT standards. All the effort at this level is a cost to produce an output (nota result), as is Level 3.

Level 2 learning is another sweet spot for the typical HPT practitioner that this model accommodates. It can include training44 if the cause of the workplace performance gap is a lack of knowledge and skills. A new software system will probably require training the workforce on how to use it. However, learning can be informational. If you change an organizational support variable, like an incentive policy, people must learn about the change and how it affects them and their work.

Therefore, learning addresses workforce knowledge and/or skill needs so people will learn what or how to change their workplace behaviors to improve the Level 4 business measures that address the needs at the organization system level.

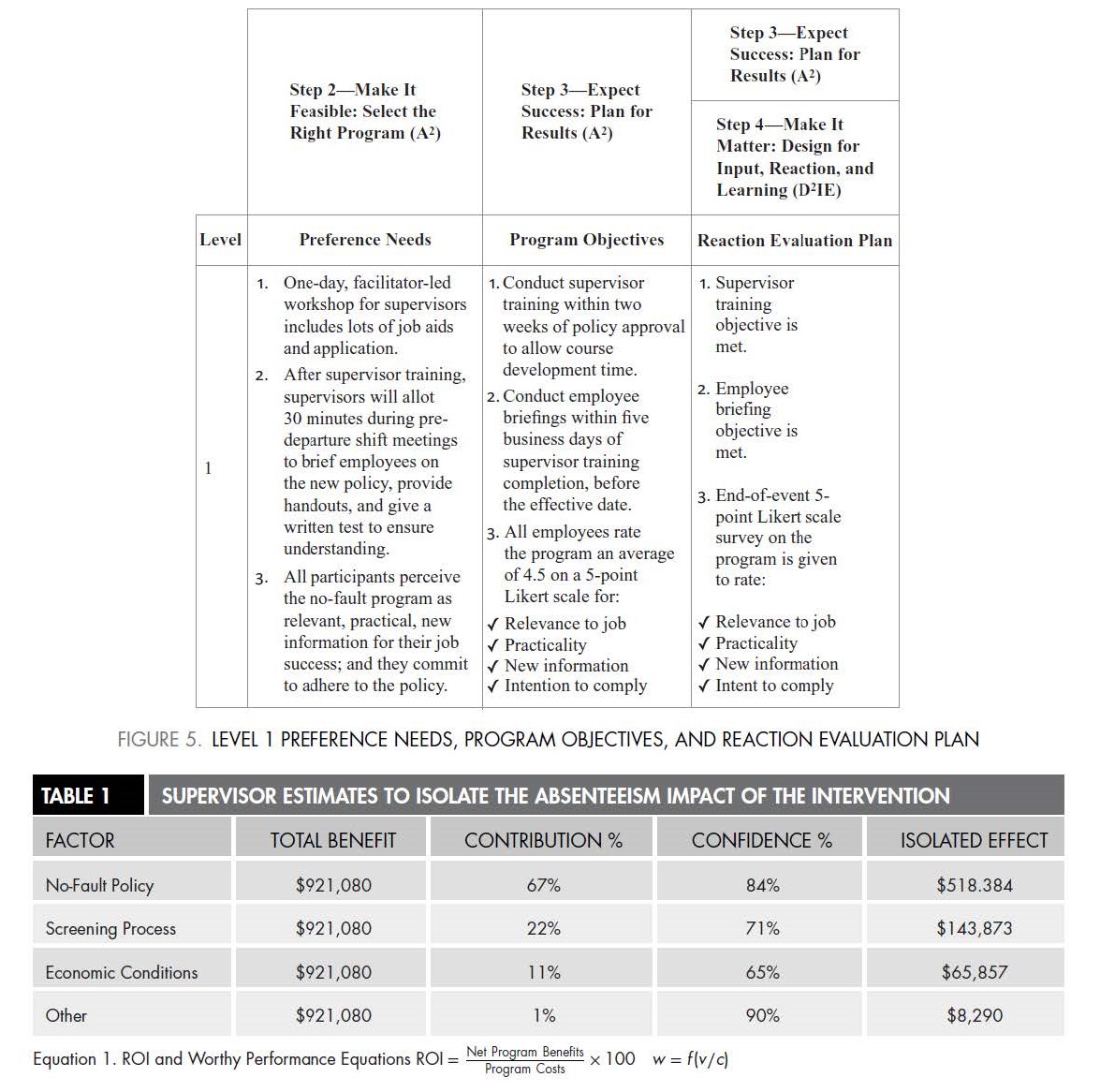

Level 1 preference needs, program objectives, and reaction-evaluation plan

For this example, the HPT practitioners collaborated with the management team to learn the preferences of the organization and supervisors to ensure a successful program implementation on a specified effective date (see Figure 5). They learned that management would permit them to create a one-day training program for supervisors to prepare them to brief their direct reports and implement the program before the effective date. They also expected everybody, overall, to react positively to the new policy and indicate an intent to comply. If the reaction is positive, they can predict it is likely they will comply with the policy on the job. If the reaction is negative, they can expect the opposite.

Level-1 preferences are where the HPT practitioner defines the needs of the people and the organization to increase the likelihood of the program’s success. Gilbert approached organization performance from a humanistic perspective with empathy toward improving conditions by improving the workplace and individual performance (Winter, 2018). This is an important basic design principle (item 4) from Table 1.

Here HPT practitioners put on the shoes of those affected by the performance improvement intervention. This human-centric perspective helps the HPT practitioner design, develop, and implement the intervention so that the program participants will perceive it as relevant and important to their job success, and they will commit to applying what they learn to their job performance. If the HPT intervention fails here, participants will not learn. If program participants do not learn, they will not change their workplace behaviors. If this happens, the business and payoff measures will not improve. As a result, the HPT practitioner’s efforts will be considered a failure.

After planning how the practitioners would evaluate the no-fault policy implementation initiative to achieve the program objectives and, by extension, to address the baseline needs, they collaborated on a communication plan that covered each phase of the process to comply with Step 7, Tell the Story: Communicate Results to Stakeholders. For process Step 8, Optimize Results: Use Black-Box Thinking to Increase Funding, they recommended how to improve the program, based on the evaluation results, as part of a continuous improvement process. These final two steps focus on improving ongoing outcomes and results.

Implementation and Data Collection

The HPT team used the identified stakeholder needs at the organization and workplace levels (along with the objectives that defined what these stakeholders expected in order to judge the intervention’s success) to design and develop the intervention. During the implementation phase, they collected objective measurement data to determine how well the program did to meet the objective at that level.

The following results demonstrate how the design- thinking-for-success process steps add Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles to ISPI’s 10 Standards for Performance Improvement. Success was determined at Standard 10, Evaluate Results and Impact, using the design-thinking process Steps 4 through 6 that were planned with the stakeholders at process Step 3.

Step 4: Make it Matter: Design for Input, Reaction, and Learning

Level 0 input

All employees were informed of the new policy and how it affected them. Appropriate resources were provided to assess, analyze, design, develop, and implement the intervention and to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiencies of the implementation’s outcomes and results.

Level 1 reaction

Overall reaction was favorable and exceeded the 4.5 Likert-scale average objective. Employees perceived the policy as equitable and fair. As expected, some employees expressed concerns. This seems to indicate a likelihood that employees will comply with the new policy, barring any application barriers.

Level 2 learning

The average true/false score was 78%. A minimum passing score of 70% was considered acceptable. Everyone left knowing the correct answers to the test and had all of their questions answered.

Step 5: Make It Stick; Design for Application and Impact

Level 3 application

A follow-up questionnaire of sampled supervisors indicated the policy was being applied consistently. Some resistance was encountered from habitual violators, but most employees still considered the policy fair and effective. Supervisors also reported that it took less time to implement this new policy than to use a progressive-discipline approach. HR records indicated that 95% of supervisors conducted the employee meeting and completed the meeting report. The new screening process was working based on sample interviews and selection records.

Level 4 impact

Bus schedule delays caused by absenteeism declined. Three months prior to the initiative, delays were 27.1%. The last three months after the intervention indicated they were down to 13.9%. In addition, before and after annualized absenteeism costs were $2,867,070 and $1,945,990, respectively. This is a cost avoidance of $921,080.

ANALYZE IMPACT DATA FOR RESULTS

Step 6: Make It Credible; Measure Results and Calculate ROI

Level 4 impact isolation

They planned to use trend line analysis to isolate the effect of the program. However, two other factors changed that could have contributed to these declines besides the no-fault policy and the new screening process. This required them to abandon this isolation approach. Since they planned to use management estimates as a back-up in

case this happened, they were able to complete this critical credibility step. Table 1 shows how supervisors estimated the effect these four factors had on the absenteeism decline and then reported how confident they were in their estimate to allow for an adjustment for estimate error (or margin of error). The isolated impact benefit for the first year was $518,384 (from the no-fault policy) + $143,873 (from the new screening process) = $662,257.

Note that the HPT team did not claim credit for the total difference of $921,080 between the pre- and post- absenteeism cost avoidance to protect the credibility of the impact they were claiming for their intervention. This is the valued performance their program delivered. This step is important because it applies ISPI Standard 3 whereby HPT practitioners provide evidence that establishes the value their program contributed to the desired impact sought by the executives. The HPT team accounted for the effect a downturn in the economy and the concomitant fewer available job opportunities might have on the impact results as they sought to improve work attendance. This is a critical, neglected credibility issue for HPT practitioners when they claim an impact result.

Convert data to a monetary value

How did the percentage decrease in absenteeism convert to monetary value? As planned at process step 3, they used the standard value of employee wages and benefits to monetize the benefit of the new no-fault policy and new-hire screening program that was implemented to reduce absenteeism costs. This standard value is how they knew how much money this absenteeism problem was costing them and convinced them to act. These calculations were completed when they isolated the impact of the program, as shown in Table 1.

Intangibles captured not converted to a monetary value

These include increased morale, improved customer satisfaction, and fewer bottlenecks in the entire system.

Program costs

The cost of the no-fault policy was $31,300. This included the costs to develop the policy, the costs of the program and training materials, and the cost of the meeting time (salaries and benefits). The cost of the new screening process was $36,100 including development costs, interviewer preparation, administrative time, and materials. It also included the cost to evaluate the program. The total program cost was $67,400.

Level 5 ROI

The ROI (or worthy performance) for this intervention was determined by the monetary benefits ($662,257) minus the program cost ($67,400) divided by the program cost ($67,400) times 100. This yields an ROI of 882%. Value for the worthy performance equation is defined as the net program benefits or program benefits minus program costs. Equation 1 displays both formulas.

Equation 1 :

ROI = Net Program Benefits/ Program Costs × 100 w = f (v∕c)

REPORT AND OPTIMIZE RESULTS

Step 7: Tell the Story; Communicate Results to Key Stakeholders

The HPT team reported the results of this intervention starting with the needs assessment at Step 1 of the design- thinking-process model and ending at Step 6 by reporting the ROI. Was this a credible ROI? Yes. The executives agreed with the financial numbers collected and computed by the finance team, as agreed during the planning stage.

Step 8: Optimize Results; Use Black-Box Thinking to Increase Funding

The HPT team also made recommendations to improve the program based on their analysis of the collected and analyzed data as compared with the program’s objectives. Doing this, the HPT team circled back to ISPI’s four-principle standards to continue to focus on results and outcomes, take a systemic view, add value, and work in partnership with clients and stakeholders to use program-evaluation evidence to make the program even better.

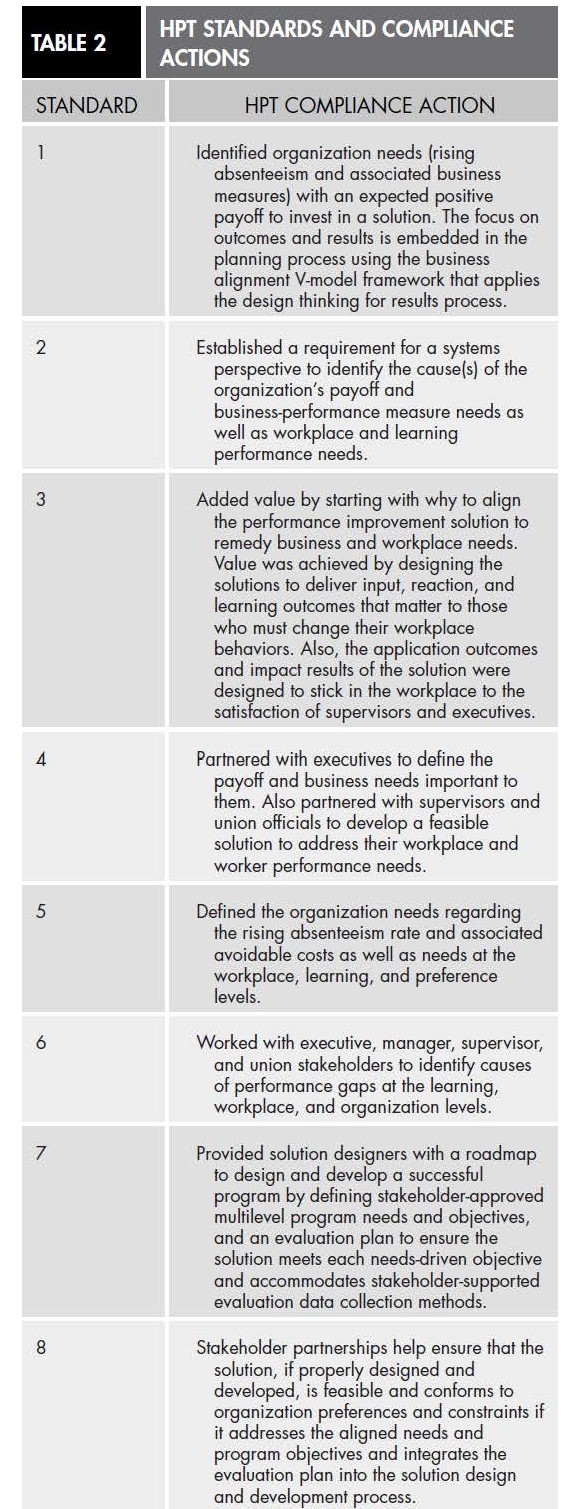

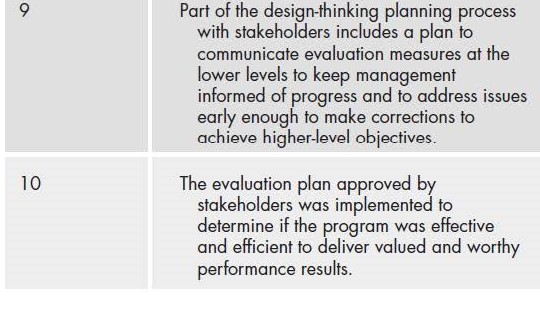

Implications for the HPT Profession

How can HPT practitioners focus on outcomes and results, the first HPT standard, if they do not plan for results and expect success? All the stakeholders must agree on what outcome and result success looks like for the intervention and commit to a role necessary for achieving and measuring that success. This is where the traditional logic model fails and where the business-alignment V- model fills that gap. Table 2 shows how this integrated- logic model addresses the HPT standards.

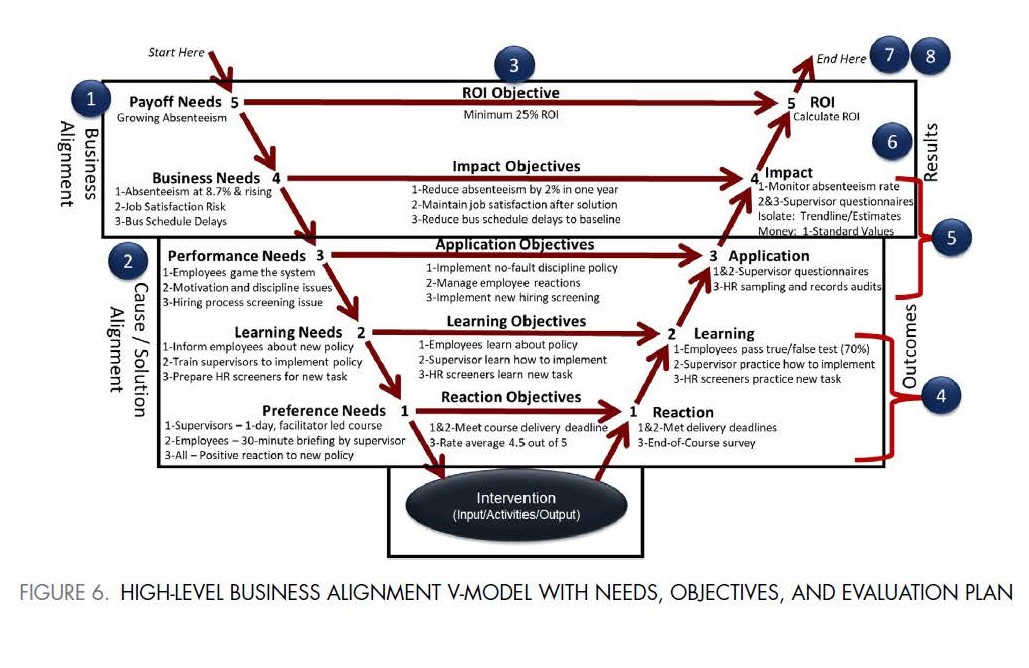

Figure 6 illustrates how the business alignment V-model, which is an HPT diagnostic intervention selection and evaluation planning tool, creates a high-level framework that shows how the design-thinking steps (the numbers in the blue dots) craft an HPT solution. Not only does it align the performance improvement needs vertically, but it also aligns the program objectives horizontally so that the HPT practitioner can evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention to address the impact (valued) and ROI (worthy) objectives that in turn address the business and payoff needs. These are the result measures that matter to executives. The HPT practitioner is establishing program (or intervention) objectives for each level in collaboration with the stakeholders and going beyond learning or performance objectives. Even more, the HPT practitioners partner with all stakeholders to define their roles and responsibilities to contribute to achieving success, as they define success with the objectives.

Executives can even decide during the planning phase to include funding for ROI forecasts as part of the evaluation plan, using data collected at Level 1 (using participant adjusted impact estimates), Level 2 (using test score/workplace performance improvement correlations), or Level 3 (using performance improvement utility analysis). HPT practitioners must plan to provide the executives with evidence that answers their performance improvement questions about the value and worth of the program they approved and funded if they so desire.

Process Step 3 is where HPT practitioners plan to do that, applying or planning for all 10 of the performance improvement standards. They are focusing on needs-driven objectives that define expected results at five levels. The HPT practitioner will evaluate the measurable indicators these objectives provide to inform them how the program is doing toward achieving the ultimate results executives want—impact (valued) and ROI (worthy) results. One of the reasons HPT practitioners struggle to evaluate new or existing programs is that they do not begin with the defined and aligned needs and objectives required to determine whether the program is delivering what it was funded to deliver. Delivering a product or implementing a program is not necessarily delivering results.

Once HPT practitioners have defined the program’s needs and objectives at these five levels, they continue to collaborate with the stakeholders to plan how they will evaluate the program to determine how well it met the needs-driven objectives so that everyone can know what worked and what must be improved at each level.

The end result is getting all of the stakeholders to agree on the elements of this business-alignment V-model and on how to collect and analyze the intervention data necessary to evaluate the effectiveness (valued performance) and efficiency (worthy performance) of the performance improvement program, project, or initiative.

Once the HPT practitioner completes the business-alignment V-model planning tool to integrate the design- thinking principles into the performance improvement effort, the HPT team is ready to design, develop, implement, and evaluate the solution. The team knows why the program was funded using business measures that matter to executives, the workplace performance needs that they must address by improving workplace performance, and how to design the program through the eyes of the participants. Together, the program is designed to meet the program’s objectives of different stakeholders at different times during the program’s implementation. Just as important, everyone knows how the HPT practitioner will evaluate the program. This will ensure that the data-collection actions required during the evaluation phase are included in the course design and development phases instead of as afterthoughts or as an unplanned expectation from management.

In summary, this advanced-logic model process that is based on design-thinking principles provides a context and framework for that work. This model helps the HPT practitioner and stakeholders see how each need identified during the needs assessment and analysis is aligned to address the need at the next level. This approach applies an important point Gilbert made: “The good engineer begins by creating a precise model of the result, then explores techniques to help in achieving those results” (1996, 105). The HPT practitioner does this by defining the needs-driven objectives that define results for each level that are defined by the key stakeholders who determine what outcomes and results success looks like at the human and organizational (or systems) perspectives.

CONCLUSIONS

Gilbert set the stage for the HPT profession by classifying what HPT practitioners do when engineering worthy performance. Gilbert was careful to build on his three principles and frame them within his leisurely theorems. This article nibbles around the edges of Gilbert’s genius without touching his argument that most of what we do to manage behavior produces incompetence. The field of performance improvement has grown beyond the original fields of behaviorism and instructional design. These professionals were early adopters of Gilbert’s work as well as the work of other pioneers within our profession. HPT professionals have matured Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles, which are integrated into ISPI’s 10 Standards of Performance Improvement. Has the HPT profession moved beyond Gilbert’s valued and worthy performance as well? Not if the HPT practitioner is truly applying ISPI’s 10 standards. ISPI begins and ends its 10 standards with results. The HPT practitioner does this by thinking like an engineer, rather than a scientist, to engineer valued and worthy performance.

Endnotes

1 This case study (Phillips, 2018) is used with the permission of ROI Institute.

2 There are respected performance improvement professionals who do not believe it is possible to isolate the effects of a program. Proven practice indicates it is not only possible but that it is a common practice at over 6,000 organizations around the globe; this is conclusive evidence that this practice is credible and expected.

3 This needs approach defines a need as a gap between the current results and the desired or required results (Kaufman & Guerra-Lopez, 2013). This approach establishes a needs-based business case to justify action to close as-is and should-be gaps. This is what the business alignment V-model does for the HPT practitioner.

4 I believe training must have three elements: presentation of what must be learned, practice doing what was presented, and feedback about how well it was done. Presenting content alone is considered a presentation, which is informational. Practice (or application) and feedback alone is considered an assessment.

References

Gilbert, T.F. (1996). Human competence: Engineering worthy performance (Tribute ed.). Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement.

Kaufman, R., & Guerra-Lopez, I. (2013). Needs assessment for organizational success. Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development.

Phillips, J J. (2018). Measuring ROI in an absenteeism reduction program. In P. P. Phillips & J.J. Phillips (Eds.), Value for money: Measuring the return on investment on non-capital investments (Vol. 1, pp. 173–186). Birmingham, AL: BWE Press, Inc.

Winter, B. (2018). Why Gilbert matters. Performance Improvement, 57(10), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21809

About the Author

TIMOTHY R. BROCK, CPT, PhD, is the director of consulting services for ROI Institute, Inc., the leading source of ROI competency building, implementation support, networking, and research. He helps organizations implement the ROI Methodology at more than 6,000 organizations in over 60 countries. He serves on the results-based management faculty at the United Nations System Staff College (Turin, Italy) and the Training and Performance Improvement faculty at Capella University (Minneapolis, Minnesota). He earned his PhD in Education from Capella University with a specialization in Training and Performance Improvement. His latest journal article, “Performance Analytics: The Missing Big Data Link Between Learning Analytics and Business Analytics,” appeared in the August 2017 issue of Performance Improvement. He may be reached at Tim@roiinstitute.net.