Your cart is currently empty!

The State of Engineering Worthy Performance and the 10 Standards: Part 1

Timothy R. Brock, CPT, PhD

This article was originally published in Performance Improvement, vol. 58, no. 10, November/December 2019.

Has human performance technology (HPT) strayed from its charter or stayed true to it? This three-part article will offer an argument that we have and offer a map to navigate back to our founding charter. This first article will review the HPT charter that Gilbert established for our profession to establish a shared understanding of our charter and review Gilbert’s eclectic-paradox warning and why it matters. This article sets the stage for the two articles that will follow.

Roger Kaufman wrote a short, thought-provoking article entitled “HPT and PI at the Crossroads” (2019). He made two points. One was that everybody seems to be jumping on the performance improvement bandwagon to help people work faster, cheaper, and better. The danger, Kaufman asserts, is a focus on individuals doing their jobs right rather than on doing the right jobs. To illustrate this point, Kaufman reminds us that the crew of the Titanic was doing a superb job of arranging deck chairs while the ship sailed into iceberg-infested waters. This leads to Kaufman’s second point. Everyone jumping on the human performance technology (HPT) bandwagon is focusing on how to improve individual performance (i.e., moving deck chairs with great skill). This is not enough. They must also align what people do with why they are doing it as part of the larger system (i.e., moving deck chairs and safe transatlantic passage). The crossroads, Kaufman argues, is the necessity to ensure that true HPT aligns the what with the why.

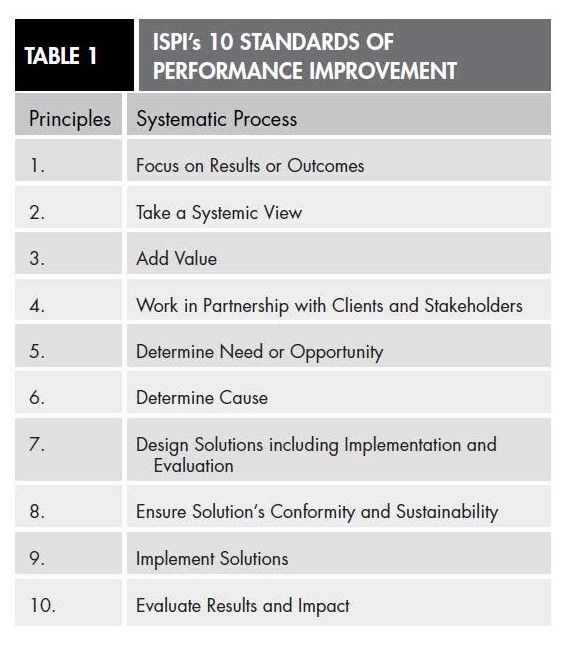

How is HPT doing as a profession standing at this crossroads? Is it more focused on arranging deck chairs than navigating safely to a defined destination? What is the why for what HPT practitioners are supposed to do? The HPT profession claims it is driven by principles and not models. The International Society for Performance Improvement (ISPI) website states that HPT is about its 10 Standards of Performance Improvement (2018) and not one model or one solution (e.g., training). The why is defined by ISPI’s first and last standards. The first standard is to focus on results or outcomes, and the last standard is to evaluate whether the intervention has achieved those results and impact. Results and impact are organizational (or system) why standards. Although these two standards are clear and clearly linked, it seems HPT practitioners are falling prey to the deck-chair syndrome.

To answer this larger why question from Kaufman, a short refresher about the why of the HPT profession’s conception is appropriate. It seems that the original why for the HPT profession was defined by Thomas Gilbert as “to engineer worthy performance.”

GILBERT’S ENGINEERING WORTHY PERFORMANCE

The genesis of the HPT profession began in the mind of Thomas Gilbert when his book titled Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance was published in 1978 (as well as a tribute edition published in 1996.) For those who are new to the HPT/performance improvement (PI) profession or unaware of who Gilbert is, Gilbert is considered the father of our profession, or at least one of the earliest pioneers of our performance improvement profession

(Van Tiem, Moseley, & Dessinger, 2012). What Gilbert wrote 40 years ago remains relevant today. Our profession’s genealogy begins with Thomas Gilbert and other genetic contributors including Skinner, Markle, Rummler, Kaufman, and others (Van Tiem et al., 2012).

Gilbert’s book title directly links human competence (the what) to engineering worthy performance (the why). Yet, Gilbert’s name is usually first associated with his behavior engineering model (BEM). The BEM is a means to an end that includes both human behavior and organizational support (or the system). Both are about the what. Rarely does “engineering worthy performance” enter the conversation except as a reference to Gilbert’s book title. I found one source that, in classifying the work of early performance improvement leaders, used “wor- thy performance” to classify Gilbert’s work (Van Tiem et al., 2012). Gilbert is much more than his BEM. He answers the why question before introducing the BEM what.

WHAT IS THE FUNDAMENTAL PURPOSE OF PERFORMANCE ENGINEERING?

Have we strayed from our why? Is our profession heading toward a Titanic end where what we do is no different from what others do to improve human performance? Yet, asking or starting with the why question is not unique to the HPT profession. What makes HPT relevant? The aim of performance engineering is “a fundamentally economic purpose” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 11). Stolovitch and Keeps (2006) assert that “HPT is bottomline and measurement conscious, imbuing it with ongoing relevance” (p. xvi). They also wrote that Gilbert often stated that HPT’s central focus is “valued accomplishment, meaning verifiable results that far exceed their costs” (p. xvi). Swanson echoes this sentiment by stating that “unless performance improvement expenditures contribute to the viability and profitability of an organization, those expenditures will almost certainly be cut back or eliminated” (2007, p. 17).

Why is HPT Principles-Driven?

Gilbert (1996) was committed to principles-driven practices derived from science. Being principles-driven remains important for us today. ISPI’s first four standards for performance improvement are the foundational, results-focused principles of practice for everything we do. Principles help guide HPT practices to address the why question.

Definitions of Principles, Standards, and Code of Ethics

First, it is important to establish a shared meaning of three common HPT terms used by practically every HPT author—principles, standards, and code of ethics. Too many authors and practitioners make the false assumption of shared meaning.

- Principles guide thinking or judgment in different circumstances or situations for us to make choices and solve They reflect basic assumptions or rules accepted as true.

- Standards, for our purposes, establish a reference point or measure to evaluate something against for comparison. A principle can serve as a standard.

- Principles also form the basis for a code of ethics to guide judgment toward making an acceptable moral decision. This is different from a code of conduct, which establishes rules for behavior in the form of do’s and don’ts.

In the Handbook of Human Performance Technology, a foundational publication of the HPT’s professional society, ISPI, Mueller states that the HPT practitioner’s work is “firmly grounded in a set of fundamental principles and a code of ethics” (2006, p. 1). In 2002, ISPI crafted and codified four fundamental principles and six process phases into the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement.

These 10 standards are the foundation of HPT as it is practiced today. These standards also establish the criterion to earn the competency-based CPT credential. The four fundamental principles and code of ethics guide how competent HPT practitioners apply the systematic process standards and their underlying practices to achieve performance results (Hale, 2007). These standards must also remain current to reflect the current, real-world practice of competent HPT practitioners to remain relevant. There- fore, ISPI revised these 10 standards in 2013 and should do so again in 2023.

How Do Principles Help the HPT Profession?

Pershing (2006) states that HPT is eclectic whereas Brethower (2008) uses the term interdisciplinary because what the HPT practitioner does crosses over into many other disciplines. Because we are so eclectic and interdisciplinary, we cannot take a one-size-fits-all approach with one model or theory. Our profession realized long ago the necessity for having standards to bring stability to what we do (Barnum, 1980). They help prevent our profession from becoming what Gilbert called “a messy jumble of eclectic ideas” (2006, p. xxxiii). ISPI established the 10 standards for serious HPT practitioners based on proven, repeatable work that distinguishes them from individuals who follow the latest fads and canards.

We must have aligned principles to drive what we do and how we do it to satisfy the why we are doing it. These principles must also spring from roots grounded in science, as advocated by Gilbert (1996), to establish an evidence-based foundation. Being principles driven means there is no one right way to apply our practices and tools. Theories and models percolating from HPT practitioners as they create their own ways to apply the 10 standards are numerous, situational, adaptable, and helpful. Pershing (2006) argues that HPT practitioners are adding eclectic and interdisciplinary theories and models that they create or adapt from other fields (e.g., organization development, human resources, change management, Six Sigma, instructional design, and technology, lean manufacturing, etc.) that require HPT practitioners to partner with these professionals and integrate their discipline within our 10 standards.

Principles Challenges—The Pershing Paradox

This can be an overwhelming challenge to some—actually, more than some. The challenge is due to something I call the Pershing Paradox. Pershing stated that, on the one hand, “drawing upon the principles and theories of numerous academic disciplines and other fields contributes to a lack of clarity for HPT” (2006, p. 29). On the other hand, Pershing (2006) asserts there is a benefit of having an eclectic and interdisciplinary profession. It allows HPT practitioners to apply their 10 standards through the lens of other disciplinary perspectives to learn from them and expand the HPT profession’s capabilities. How can the HPT practitioner assimilate new and helpful principles and practices without adding to this lack of HPT clarity? A better question is How can we integrate new perspectives that can improve both our HPT clarity and our worthy performance potential?

This paradoxical dilemma of trying to manipulate a multitude of possible permutations to create a clarity of perspective is often missed by students learning HPT and struggling HPT practitioners who are not familiar with the HPT literature. Even worse, too many times it is not uncommon to witness emerging HPT practitioners and seasoned practitioners who should know better (the latter based on research by Leigh, 2014) as they try to force a favorite or familiar “round” model or theory into a “square” situation that lets them crank out a comfortable, business-as-usual solution without much thought or reflection about evidence suggesting otherwise.

Many HPT practitioners excel with one phase of the six process phases of HPT. Unfortunately, they are hit-and-miss with the four foundational principles that influence how to apply these six process phases. Brethower (2008) correctly asserts that projects that do not include all four principle standards are not HPT projects. HPT practitioners may limit their work scope to one or more of the systematic process standards, but the four foundational principle standards are not negotiable. Why is that? To answer this, we must look at the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement.

ISPI’S 10 STANDARDS OF PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT

Table 1 lists ISPI’s 10 Standards of Performance Improvement used by HPT practitioners and certified performance technologists (CPTs) around the world (International Society for Performance Improvement, 2018). As already noted, the first four principle standards influence the six systematic process standards. (For those unfamiliar with, or who would benefit from a refresher of these 10 standards, the following URL provides a detailed description of each standard and the Code of Ethics: ispi.org/ISPI/Get_Certified/CPT_Certification/CPT_Standards/ISPI/Credentials/CPT_

Certification/CPT_Standards.aspx.)

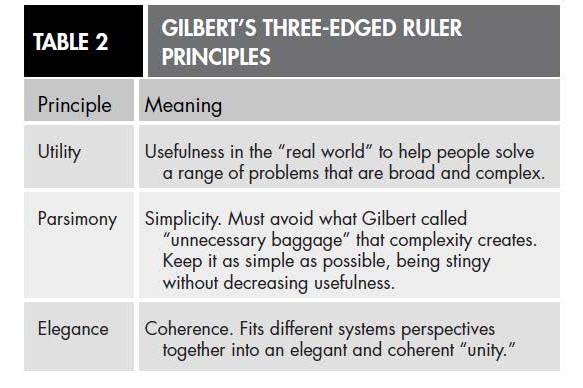

GILBERT’S THREE-EDGED RULER PRINCIPLES

Even more, these 10 ISPI standards are rooted in three fundamental operating principles from science that Gilbert called a three-edged ruler—parsimony, elegance, and utility (Gilbert, 1996). Dean (1996) wrote that Gilbert would always explain these three principles before talking about his work. Gilbert (1996) does the same in the first three pages of his book. Table 2 lists these three-edged ruler principles and what Gilbert meant by each one.

Therefore, HPT practitioners should always begin by ensuring their work is based on performance improvement principles and process standards that measure up to Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles to engineer worthy performance. ISPI’s response is its 10 HPT standards.

Why are these principles-driven standards critical to our success? The “should-be” state of the HPT profession requires a situational approach, whereby the HPT practitioner is guided by the four-principles standards and the code of ethics to address a multitude of proven practices across a full spectrum of disciplines as the evidence dictates. Then again, HPT cannot be all things to all people. That is why there is a standard principle to address this (i.e., partnering). Maybe the HPT profession should “stick to the knitting” of what makes it unique (Peters & Waterman, 1982). This brings us back to the earlier question about what makes us relevant and unique. It is why we do what we do—engineer worthy performance.

WHAT IS ENGINEERING WORTHY PERFORMANCE?

Because Gilbert coined this phrase in his book to define our profession, let’s review what he meant by each term.

Definitions of Engineering, Performance, and Worthy Engineering

Engineering methods are the opposite of scientific methods. Engineers use whatever methodology will get them precisely to where they want to get to. They start with an end in mind and focus on results. Scientists, however, follow their methodology to wherever it leads (at least they are supposed to do it this way). The methods that engineers adopt to improve engineering results come from the “new knowledge that science creates and by arranging existing knowledge into simpler and more powerful systems” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 4). Therefore, engineering is a logical and pragmatic extension of science and applies Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles. This is a reason we assert that HPT is rooted in science, to equip us to engineer worthy performance. However, we are not “science-based,” as some suggest.

Performance

Gilbert (1996) described performance as the consequence of improved human behavior. We want to engineer valuable performance that is a consequence of behavior. Behavior is an integral part of the performance. Behavior is a means to arrive at performance. How do we decide which behavior to change? Gilbert stated that we should not change behavior unless someone places a value on the consequences of that behavior. Performance is possible without value, but it is wasted effort. Gilbert even created what he called a shortcut to represent this relationship. The shortcut is represented by an equation where performance (P) is what you get when a behavior (B) leads to a consequence (C), or P = B → C. Gilbert later changed consequence to accomplishment (A), or P = B → A.

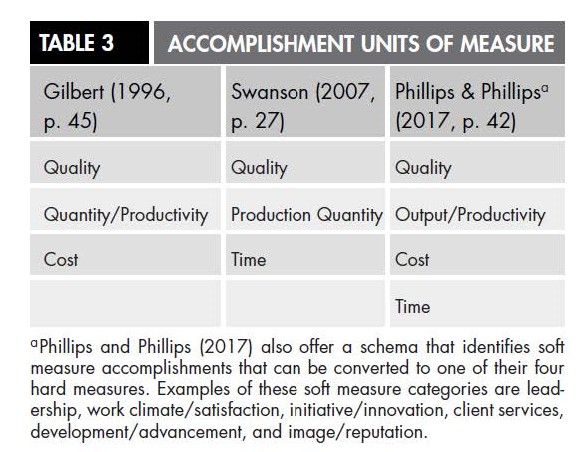

Accomplishments as units of measure

Gilbert preferred to use the term accomplishment for the consequence of changed behavior because this term is associated with value. Gilbert (2006) believed outputs or results are not necessarily associated with value because they can be irrelevant or undesired or worse. To engineer performance, we must have “quantifiable measures of performance, not of behavior” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 70). What do performance measures look like? Table 3 lists the three accomplishment-measurement categories that Gilbert identified. Gilbert’s measures are similar to the accomplishment measures defined by analysis, measurement, and evaluation experts, who refer to them as units of performance, business impact measures, or key performance indicators. These are the organizational measures we want to engineer human performance to improve.

It is important to remember that performance is not behavior. Similarly, “performance is not system design, capability, motivation, competence, or expertise,” which are considered performance variables (Swanson, 2007, p. 27). A stakeholder must attach value to a performance accomplishment (Addison, Haig, & Kearney, 2009; Gilbert, 1996; Pershing, 2006; Stolovitch & Keeps, 2016; Swanson, 2007). Gilbert was clear on this when he wrote, “When we set about to engineer performance, we should view it in a context of value” (1996, p. 17). Stakeholders routinely ask, “so what?” when you have changed workplace behaviors. They want to see an improved accomplishment measure that they value. Addison, Haig, and Kearny (2009) speak to this when they define performance as “activity plus results plus value.” An HPT task force added, “people working within a system” as another variable to the performance definition (Pershing, 2006, p. 38). However, if people are working within a system to achieve a result, but the result is not valued, then so what? As Gilbert (1996) originally stated, HPT is about engineering valuable performance. After all, if no one values the accomplishment, why are we spending money for it? As Swanson puts it, “Performance improvement cannot occur in a vacuum” (2007, p. 81).

Worthy

Gilbert goes one step further than engineering valuable performance. That next step is to engineer worthy performance where the value of the performance result achieved exceeds the cost of improving the antecedent behavior (Gilbert, 1996). The higher the value when compared to the cost, the higher the worth. Gilbert (1996) stated that those who are competent create value greater than the cost of their behavior (ergo, the title of his book, Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance). In other words, competent people are known by their valuable and worthy performance. Therefore, competent performance improvement programs, projects, and initiatives are known by their valuable (i.e., improved units of performance or business measures) and worthy (aka benefit-cost ratio (BCR) or return-on-investment (ROI) results that are the consequence (or accomplishment) of improved human competence.

In addition, when comparing a scientist to an engineer, Gilbert stated a second key difference. An engineer “sees knowledge as a costly means that should be applied efficiently, if the costs are not to distract from the valuable ends” (1996, p. 4). Gilbert was clear to include costs as an engineering variable when something is being improved because efficiency is as important as effectiveness. Gilbert was clear about why he chose the term engineering when he wrote that “engineering is always a system to manipulate things” (1996, p. 7). What we manipulate (or influence) is human behavior.

Gilbert was concerned about both the costs and the benefits of performance-engineering efforts. The costs represent how efficient the HPT practitioner was in engineering a valuable accomplishment. The benefits represent how effective the HPT practitioner was in engineering a valuable accomplishment. To be clear, for those who approve and fund performance improvement initiatives, “value equals money” (Phillips & Phillips, 2018, p. 217.) More about that appears further along.

Telenomics, the Forgotten Term

Gilbert even coined a term, telenomics, to cement the case that his focus included both effectiveness and efficiency. The term combines two Greek words that mean the “laws” (nomos) of “ends” (teleos)” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 10). Telenomics represents Gilbert’s performance engineering system that involves three phases studying, measuring, and engineering human competence” (1996, p. 10).

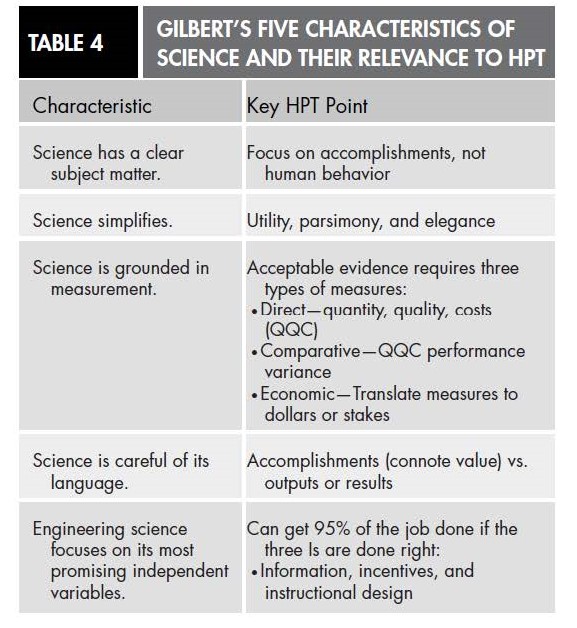

Gilbert argues that a purpose of engineering systems is economic (see Table 4) where worth is fundamentally the ratio of the effectiveness (accomplishments) and efficiency (costs) of the engineered performance (1996, p. 106).

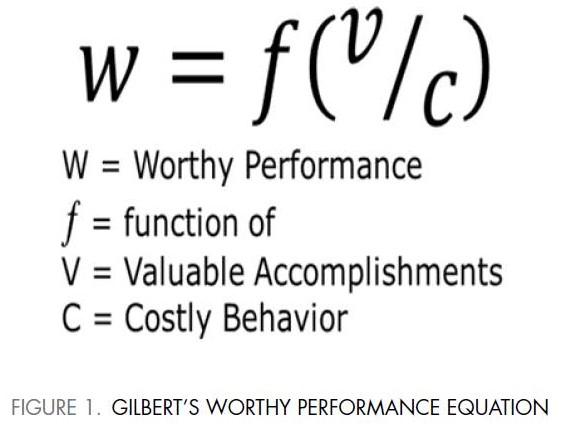

Worthy Performance Formula

To calculate this effectiveness/efficiency ratio, Gilbert created a formula (see Figure 1) in which the numerator is the effectiveness value (i.e., accomplishments or results) and the denominator is the cost (i.e., of the behavior). It defines human competence as a function of worthy performance and implies that worthy performance is a function of the value of the accomplishments divided by the cost of the behavior. The numerator is the accomplishment value (how effective the performance engineering effort was to create valued accomplishments). The denominator is the cost of the changed behavior (how efficient the performance engineering effort was to deliver valued accomplishments) (Gilbert, 1996; Phillips & Phillips, 2018). This is simple math. Getting the cost numbers and monetizing the numerator are the challenges.

What Do These Definitions Tell Us?

Based on these three definitions (engineering, performance, and worthy), it seems that Gilbert argued that improved performance resulting from changed human behavior must deliver value beyond the resulting accomplishments. The value must also exceed the cost of achieving the resulting accomplishment to be considered wor- thy. This is the HPT practitioner’s true-north compass heading that helps navigate safe passage to the destination defined at ISPI standards 1 and 6—valued and worthy performance.

How does the HPT profession stay aligned to Gilbert’s true north to focus on engineering worthy performance as Gilbert defined it? Even more, has the HPT profession stayed on course, or has it drifted away from the worthy standard Gilbert established as foundational to the purpose of HPT? In his tribute to Gilbert, Dean (1996) argues that a lot of Gilbert’s work has been eclipsed by the passing of time from the more recent work of others who use Gilbert’s work as the starting point for their own (p. 10).

Has Gilbert’s work been eclipsed and, if so, is that a positive? A good starting source for an answer is the Handbook of Human Performance Technology: Principles, Practices, Potential (aka the HPT Handbook) that was published by ISPI.

When Gilbert wrote the Foreword to the first edition of the HPT Handbook, he emphasized the technology element of the term HPT. He stated that technology “is a system that applies the best techniques and sciences to a subject matter” and that “science is at the base of technology” (2006, p. xxxiii). Gilbert then discussed five characteristics of science that are foundational for our profession to claim that our engineering (aka HPT) standards are rooted in science (2006, p. xxxiv). They are summarized in Table 4. (Note: In the first edition of the book, Gilbert’s original Foreword included two characteristics of science that were not included in the second and third editions. Those two characteristics were “Science Depends on Observation, Not Hearsay” and “Science Is Guided by Evidence.” These two characteristics were not included in Table 4 to reflect Gilbert’s revised list of characteristics.)

Interestingly, Gilbert included economic measures to monetize quantity, quality, and cost (QQC) variation measures that we first saw in Table 3. In this context, a performance variation is a difference between the baseline and post-intervention QQC measures (i.e., accomplishments). The economic measures include the costs associated with changing human behavior to produce valued accomplishments. These three measurement characteristics include the variables of the worthy performance calculation (i.e., QQC business benefits that are the consequence of improved human behavior and the costs to achieve them).

How important was this to Gilbert? A book title is carefully crafted to represent the thesis of the entire book. In other words, if you were asked to summarize a book in a few words, what would you say? Why not start with the book title? Why did Gilbert write his book? He wrote it to explain his system to engineer improved human competence and worthy performance. Gilbert goes on to write: “The system this book describes is based on three theorems summarizing my major assumptions about the nature of human competence” (1996, p. 15).

GILBERT’S THEOREMS OF ENGINEERING WORTHY PERFORMANCE

It is common to read that Gilbert had three theorems. It seems he had one core theorem and three corollary theorems.

Core Theorem: Human Competence Is a Function of Worthy Performance

Gilbert (1996) stated that his core theorem was critical because it accomplishes two things. First, it defines worthy performance and human competence. Second, it makes the case that it is important to distinguish between behaviors and accomplishments. Gilbert was clear when he wrote that “competent people are those who can create valuable results without using excessively costly behavior” (1996, p.17). His first theorem defines human competence as “a function of worthy performance” (1996, p. 18). Gilbert expressed this theorem as a formula (see Figure 1). Gilbert argued that this theorem “is the key toa system of engineering human performance” (1996, p. 18) and that his other three theorems come from this one. This first theorem has three economic corollary theorems to produce meaningful performance measures.

First Economic Corollary: Worth Reflects the Ratio Between Accomplishment, Value, and Costs

The first economic corollary focuses on worthy performance by asserting there is a difference between measures of accomplishment and measures of behavior. Only accomplishment measures “can be converted into a dollar return” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 22) and have direct value. People invest in getting accomplishments. Behavior change costs money. Worth reflects the ratio between the expected cost of the investment to improve an accomplishment (value) and the cost of the changed behavior required to achieve those accomplishments. A positive BCR is when the ratio between the accomplishment value (i.e., benefit) and behavior costs exceeds 1.

Second Economic Corollary: Measuring Accomplishments Precedes Measuring Behaviors

Gilbert’s second economic corollary (aka measurement theorem) is about the potential to improve performance. Gilbert states, “We have no need to measure behavior until we have measured accomplishment” (1996, p. 23). This measurement theorem establishes the foundation for engineering worthy performance. Before we consider the cost of an investment to improve behavior, we must first consider the potential value of the return on the accomplishment measure. This is where Gilbert talks about his potential for performance (PIP), which is an opportunity measure that establishes the criterion for valued performance. Engineering worthy performance begins with determining the opportunity potential from improving accomplishments of typical performance to the

performance of exemplars (if exemplars exist). Gilbert defined exemplary performance as “the most sustained worthy performance that we can reasonably expect to attain” (1996, p. 45). The greater the difference between typical and exemplar performance, the greater the PIP. It determines the current level of performance and the potential opportunity for improvement.

Gilbert distinguishes PIP as a measure of human potential against an IQ test. The IQ test focuses on behaviors and views of those with the highest scores as having the greatest potential. PIP, however, focuses on performance and views the greatest potential to those with the lowest scores. PIP does something about this potential where the IQ test does nothing. Gilbert makes a compelling statement that he takes a humanistic view that “sees people for what they can do, and not for their limitations” so they can “improve their condition” (1996, p. 70). Gilbert states that the worthy performance used as accomplishment measures involve “quality, quantity (or productivity), and cost” (1996, p. 45) (see Table 3). What is missing is the economic value of this potential to improve performance. To do this, Gilbert argues we must translate this potential performance measure into what he calls “stakes” where “stakes are the money value of realizing the PIP” (1996, p. 32).

Third Economic Corollary: Valued Performance Is a Result of Behavior and Environment

The third economic corollary, which introduces his behavior engineering model, has two parts. The first part asserts that when behavior measures are expressed as numbers (quantitative measures), they are often misleading indices of performance. There are special circumstances where this is not true, but they are the exception, not the norm. Gilbert makes the point that most test scores are misleading measures of behavior unless they are linked to accomplishment measures that occur in the workplace. A linear correlation using test scores and workplace performance measures does that. It also allows us to forecast an estimated BCR or ROI (i.e., worthy performance).

The second part states, “It is frequently useful to quantify measures of accomplishment, and these measures should have economic correlatives” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 24). Gilbert’s point is that there are many behaviors that contribute to failed or improved performance, but only some matter or make a difference. Rather than compile a list of behaviors to change, focus on the ones that someone says have value because they matter. As Gilbert put it, “Measures of accomplishment have no real validity until they reflect value to someone, and the dollar currency is one excellent way to express this value” (1996, p. 25). How do we know someone values something? When they are willing to pay for it and expect a positive return on their investment. It starts with value. We value the accomplishments of behavior, not the behavior. Behavior is one condition of performance. The second variable is environmental support. This is where Gilbert’s behavior engineering model enters the scene. It was developed as a diagnostic tool to “order our thinking about how we can alter performance through changes in behavior” (Gilbert, 1996, p.83). Three are environmental (information, instrumentation, and motivation), and three are behavioral (knowledge, capacity, and motives). The model does not tell us how to engineer worthy performance.

Gilbert expressed his behavior engineering model as an economical equation where worthy performance equals value (accomplishments) divided by costs. These costs include the cost for the improved behavior plus environmental support costs and the costs for the management system. Despite these cost variables, Gilbert’s point from the beginning is that “a small investment in behavior can yield great returns in accomplishment” (1996, p. 88).

Why Did Gilbert Use the Term Leisurely Theorems?

Gilbert referred to his theorems as “leisurely theorems.” Gilbert explains that the term leisure is from a historical French word meaning permission, as in when people have permission to break away from mundane work, freeing them to get other things done in the same amount of time. Leisure represents the opportunity to get more done before it is too late. Who does not value the time and opportunity to get more done? The product of leisure is time and opportunity.

Gilbert helps us understand what he means when he writes, “Opportunities with time to pursue them mean nothing. And time, dead in our hands, affording no opportunities, has even less value” (1996, p. 11). Gilbert asserts that leisure is “the worthy aim of a system of performance engineering, and the one I consider to be its true purpose” (1996, p. 11). Put in different words that emphasize the main title of his book, “The very purpose of competent human performance, then, is leisure itself ” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 26). We can consider worthy performance as improving leisure, where opportunity is defined as desired accomplishments involving hard or soft business measures. Because the meaning of the term leisure has come to mean something different than time and opportunity, Gilbert uses the term human capital to mean the product of time and opportunity. As Gilbert puts it, “The beginning point of performance engineering is, therefore, human potential; its endpoint is the increase of human capital” (1996, p. 12). Increasing human capital, then, is the purpose of performance engineering and its starting point.

Why is this important? Gilbert states that, if we view performance engineering using a teleonomic perspective, “all values are derived from the ultimate worth inherent in human capital” (1996, p. 313). Human capital, therefore, is about valued and worthy organizational results (Gilbert, 1996; Phillips & Phillips, 2015). If you do not know what Gilbert means by human capital, you cannot understand his meaning for value or the context of his three leisurely theorems. If you do not know or understand how Gilbert defines human capital, you cannot know or understand what he means by engineering worthy performance. It is a human-centric perspective. It is about the economics of increasing leisure results (accomplishments) that add value to the business while simultaneously minimizing the costs (money) to increase the more productive leisure time and opportunity (Gilbert, 1996).

STATE OF THE HPT PROFESSION

Between the 14 years since Gilbert first published his Human Competence book in 1978 and when he wrote the Foreword for the first HPT Handbook in 1992, he made sure to include measurement as a foundational principle that included economic measures required to calculate worthy performance. Did Gilbert’s worthy performance cornerstone stand the test of time when the third edition of the HPT Handbook was published in 2006, another 14 years later?

The Foreword to the third edition, written by Stolovitch and Keeps, who were the editors of the first two HPT Handbook editions, states that HPT “is a professional field of study and application, the purpose of which is to engineer systems that allow people and organizations to perform in ways that they and all stakeholders value” (2016, p. xiii). This definition of HPT includes the terms engineer, perform, and value (p. xiii). A term not included is worthy. Yet, the first two of the six reasons they list in explaining why they conclude that HPT is a valuable, wor- thy, and enduring practice rather than a fad is because of HPT’s “concern with bottom-line results and Return on Investment (ROI) issues” and “the high stakes of high investments” (Stolovitch & Keeps, 2016, p. xvi). The term investment is important because it implies a positive return. Otherwise, it is a cost. Investments imply a return. Everyone wants their 401(k) to be an investment rather than a cost. HPT practitioners must pay as much attention to the costs of changing behavior as they do their valued accomplishments to remain relevant (Stolovitch & Keeps, 2016).

To summarize, using Gilbert’s definitions, especially his human competence/worthy performance equation, “If human competence resides in behavior, then to set about to engineer human competence means that we must manipulate human behavior since engineering is always a system of manipulating things” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 7). Why do we manipulate behaviors? To achieve worthy performance. That is our ultimate challenge.

Back to the Pershing Paradox

Two comments by Pershing mentioned previously indicate that Pershing framed this challenge (either intentionally or unintentionally) as a paradox. This paradox is a consequence of adding the principles, theories, and practices of other disciplines and fields. Pershing (2006) asserts that we have become an eclectic, elastic profession. How- ever, we risk losing the clarity of why we exist—to engineer worthy performance.

Even more, the elasticity of this eclectic profession continues to grow as it continues to partner with established and emerging professions and disciplines (e.g., organizational development, human resources, instructional design, lean manufacturing, Six Sigma, etc.) that are also focused on delivering solutions to improve human and organizational performance (Pershing, 2006, p. 29.) The risk to this path is that HPT may become a hodgepodge profession trying to be all things to all people to gain acceptance as a real profession. Instead, HPT practitioners should advocate what makes the profession unique in order to attract like-minded professionals from other disciplines to integrate the HPT standards into their own because HPT offers something missing from their performance improvement frameworks. It is not about arranging deck chairs.

CONCLUSION

Now is an excellent time to reconsider Gilbert’s admonition on this subject: “Although eclectic systems may sometimes be useful, they seldom have the simplicity and never the elegance that I have held as criteria for success. … But eclectic systems do have one sensible quality that all who offer ideas might envy. They know there is more than one way to look at the world” (Gilbert, 1996, p. 5). Part 2 of this article will do this by exploring how the work of Gilbert and principles for design thinking from the field of innovation provide a different way to view a performance improvement need or opportunity and to do so with a renewed level of simplicity and elegance that enables a return to the state of clarity required to engineer worthy performance.

References

Addison, R., Haig, C., & Kearney, L. (2009). Performance architecture: The art and science of improving organizations. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Barnum, T.M. (1980). Imperative: We must have standards! Performance Improvement, 19(2), 2.

Brethower, D.M. (2008). Historical background for HPT certification standard 2, take a systems view, part 1. Performance Improvement, 47(7), 7. 10.1002/pfi.183

Dean, P. (1996). Foreword. In Human competence: Engineering worthy performance (Tribute ed.). Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement.

Gilbert, T.F. (1996; 1978 Tribute ed.). Human competence: Engineering worthy performance. Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement.

Gilbert, T.F. (2006). Foreword. In J.A. Pershing (Ed.), Handbook of human performance technology: Principles, practices, potential (pp. xxxi–xxxv). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Hale, J. (2007). The performance consultant’s fieldbook: Tools and techniques for improving organizations and people (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

International Society for Performance Improvement. (2018). What is performance improvement?Retrieved from https:// www.ispi.org/ISPI/Our_Society/About_ISPI/Performance_ Improvement/ISPI/About_ISPI/What_is_Performance_ Improvement.aspx?hkey=dc6249a4-7449-48fd-a2d5-99583 a124580

Kaufman, R. (2019, March). HPT and PI at the crossroads. PerformanceXpress (ISPI newsletter).

Leigh, H.N. (2014). The road taken: A between and within subjects study of intervention by performance improvement professionals. DAI-A 76/04€, Dissertation Abstracts International. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Full Text, Ann Arbor.

Mueller, M. (2006). Foundations of human performance technology. In J.A. Pershing (Ed.), Handbook of human performance technology: Principles, practices, potential (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Pershing, J.A. (2006). Human performance technology fundamentals. In J.A. Pershing (Ed.), Handbook of human performance technology: Principles, practices, potential (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Peters, T.J., & Waterman, R.H., Jr. (1982). In search of excellence: Lessons from America’s best-run companies. New York, NY: Warner Books.

Phillips, P.P., & Phillips, J J. (2015). Making human capital analytics work: Measuring the ROI of human capital processes and outcomes. New York. NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Phillips, J.J., & Phillips, P.P. (2016a). Handbook of training evaluation and measurement methods (4th ed.). New York, NY: Gulf Publishing Company.

Phillips, P.P., & Phillips, J.J. (2016b). Real world training evaluation: Navigating common constraints for exceptional results. Alexandria, VA: ATD Press.

Phillips, J.J., & Phillips, P.P. (2017). The business case for learning: Using design thinking to deliver business results and increase the investment in talent development. West Chester, PA, and Alexandria, VA: HRDQ and ATD.

Phillips, J.J. and Phillips, P.P. (2018). The value of innovation: knowing, proving, and showing the value of innovation and creativity. Hoboken, NJ, John Wiley & Sons.

Stolovitch, H.D., & Keeps, E.J. (2006). Foreword. In J.A. Pershing (Ed.), Handbook of human performance technology: Principles, practices, potential (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Swanson, R.A. (2007). Analysis for improving performance: Tools for diagnosing organizations and documenting workplace expertise (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

Van Tiem, D.M., Moseley, J.L., & Dessinger, J.C. (2012). Fundamentals of performance improvement: Optimizing results through people, process, and organizations (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

About the Author

TIMOTHY R. BROCK, CPT, PhD, CRP, is the director of consulting services for ROI Institute, Inc., the leading source of ROI competency building, implementation support, networking, and research. He helps organizations implement the ROI Methodology at more than 6,000 organizations in more than 60 countries. He serves on the results-based management faculty at the United Nations System Staff College (Turin, Italy) and the Training and Performance improvement faculty at Capella University (Minneapolis, Minnesota). He earned his PhD in Education from Capella University with a specialization in Training and Performance Improvement. His journal article, “Performance Analytics: The Missing Big Data Link Between Learning Analytics and Business Analytics,” appeared in the August 2017 (Volume 56, Issue 7) Performance Improvement Journal published by the International Society for Performance Improvement (ISPI). He may be reached at Tim@roiinstitute.net