Your cart is currently empty!

The State of Engineering Worthy Performance and the 10 Standards, Part 2

By Tim R. Brock, CPT, Ph.D.

This article was originally published in the February 2020 issue of Performance Improvement.

Abstract

Part one of this three-part series suggested that the human performance technology (HPT) profession has strayed from its charter as established by Gilbert, a recognized founder of HPT. This second article offers a solution for the eclectic jumble of ideas that can confuse the work of HPT practitioners as they apply the 10 standards. This new lens comes from the field of innovation that brings greater HPT clarity and meets Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles discussed in part one.

Part one of this three-part series ended with a paradox. This paradox is the unintended result of the human performance technology (HPT) profession growing in complexity by adding the principles, theories, and practices of other disciplines and fields while also gain- ing new perspectives from them. Pershing (2006) asserts that we have become an eclectic, elastic profession but that we risk losing the clarity of why we exist—to engineer worthy performance. Even more, the elasticity of this eclectic profession continues to increase as the profession continues to partner with established and emerging professions and disciplines that are similarly focused on delivering solutions to improve human and organizational performance (Pershing, 2006). The risk is that HPT is becoming a hodgepodge of a profession, trying to be all things to all people to gain acceptance as a real profession.

Part one concluded that HPT practitioners should advocate what makes their profession unique in order to attract like-minded professionals from other disciplines to integrate the HPT standards into theirs because HPT offers something missing from their performance improvement frameworks. It ended with this admonition from Gilbert (1996): “Although eclectic systems may sometimes be useful, they seldom have the simplicity and never the elegance that I have held as criteria for success. … But eclectic systems do have one sensible quality that all who offer ideas might envy. They know there is more than one way to look at the world” (p. 5).

Part two explores how the HPT profession can add a new way to look at the world while returning to the elegance and simplicity the profession advocates by integrating design thinking principles from the world of innovation.

GILBERT’S SOLUTION TO THE PERSHING PARADOX

Perhaps it is time to recalibrate HPT’s professional lens using Gilbert’s (1996) three-edged ruler principles to provide a simpler framework for applying our HPT principles and process standards. Why not consider a lens that brings a level of utility, parsimony, and elegance to our evolving, eclectic role as HPT practitioners?

Pershing (2006) argued that the key drivers of HPT are evaluation and change to improve organizational results. Further, Esque (1996) stated, “The first rule of engineering worthy performance [is] get clear about valued accomplishments” (p. 12). As discussed previously, Gilbert (1996) stated, “The purpose of performance engineering is to increase human capital, which can be defined as the product of time and opportunity” (pp. 11–12). Finally, Gilbert (1996) reminds us, using engineering terms, that “the good engineer begins by creating a precise model of the result, then explores techniques to help in achieving those results” (p. 105). That achievement process begins with Esque’s first rule of engineering and continues with Pershing’s managing the change and evaluation processes to determine whether the HPT practitioner has achieved the desired results.1

Perhaps a new three-edged ruler lens will help us gain greater clarity about how to define, deliver, and evaluate worthy performance. Perhaps returning to HPT’s engineering foundation will require some reverse engineering. What is the ultimate outcome or result of the HPT engineering efforts? Worthy performance. What is necessary for HPT practitioners to engineer (to improve) before arriving at the worthy performance? Valued performance. What must the HPT practitioner engineer before arriving at the valued performance? Improved performance behaviors. Worthy (Aw) and valued (Av) performance (both considered accomplishments) are a consequence of improved performance behaviors (B). Put another way, HPT = B → Av → Aw. This logic chain reflects Gilbert’s core leisurely theorem. It seems that most definitions of HPT or performance improvement seem to focus on valued performance. This formula indicates that worthy performance has somehow lost its unique status and has become buried in the value family. I believe Gilbert might have taken issue with this development.

To engineer behaviors using Gilbert’s (1996) second economic corollary theorem (aka the measurement theorem using the potential for improving performance (PIP) ratio), Gilbert’s third economic corollary theorem (aka the efficient behavior theorem using the behavior engineering model (BEM)) indicates that the HPT practitioner must consider six factors that influence human behavior. Three of these factors reside in the organization, and three reside in the individual. Each factor costs money to improve and sustain. HPT practitioners are eager to get to the performance-analysis phase of the HPT model advocated by Van Tiem, Mosely, and Dessinger (2012), where interventions emerge from a cause analysis using Gilbert’s BEM (or another model). Instead, perhaps, the HPT practitioner should first take advantage of the different lenses offered by other disciplines to do two things. The first is to expand the practitioner’s capabilities that Pershing (2006) asserted was an advantage of HPT’s eclectic profession. The second is to satisfy Esque’s (Gilbert, 1996) first rule of engineering worthy performance. As Gilbert (1996) put it, “Although eclectic systems may sometimes be useful, they seldom have the simplicity and never the elegance that I have held as criteria for success. But eclectic systems do have one sensible quality that all who offer ideas might envy. They know there is more than one way to look at the world” (p. 5).

PRINCIPLES FOR INNOVATION AND HPT

Organizations are expecting investments in performance improvement efforts to mature both organization and human performance. This is also true for investments in innovation. These are not science projects. Investors expect results for their money. How do you design innovations that deliver measurable results when you are held accountable for proving the value (financial and nonfinancial) return of innovation investments? Without realizing it, innovation professionals have adopted Esque’s position for engineering worthy performance into their design-thinking assumptions to achieve measurable, valued, and worthy results.

To design successful innovation projects, you must clearly define success for collaborative innovation teamwork. Whether the innovation was intended to improve quality, reduce costs, improve functionality, or even discover a disruptive new product or business model, success is achieved when the desired impact (or valued accomplishment) is achieved in return for the investment (Phillips & Philips, 2018).

PRINCIPLES FOR DESIGN THINKING FOR RESULTS

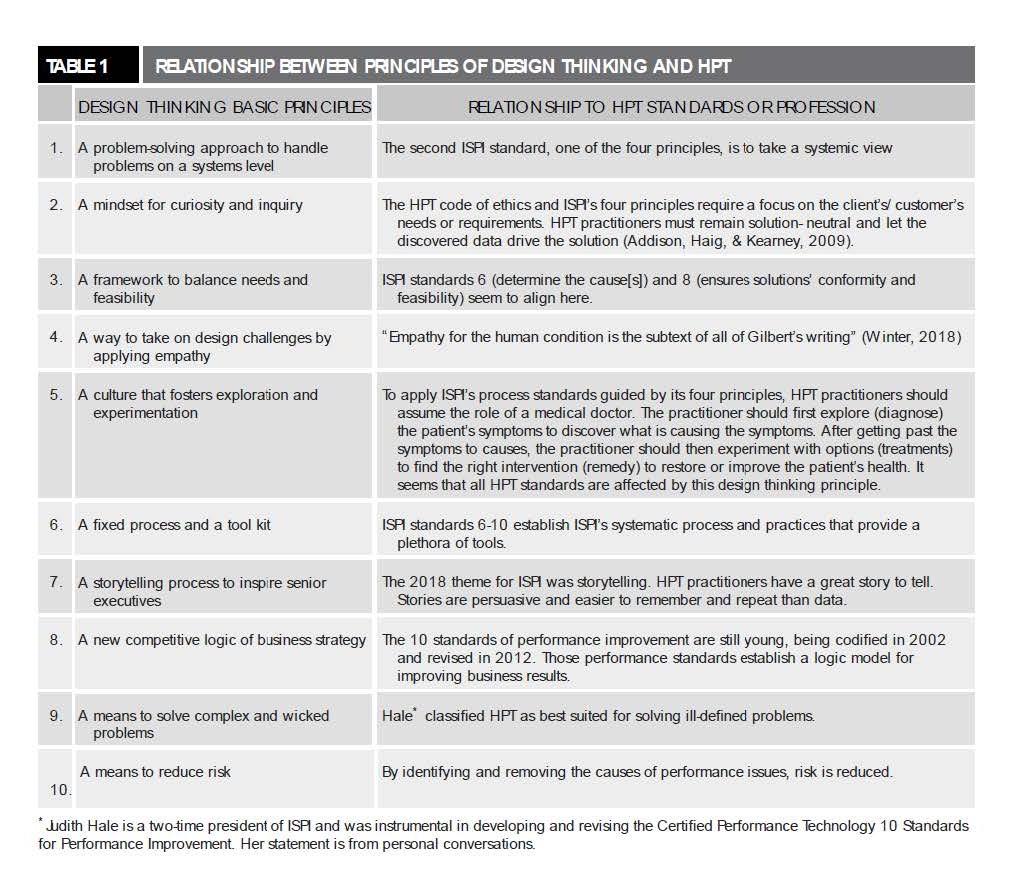

A set of principles for design thinking has emerged that compares well with ISPI’s 10 standards and the HPT profession. Although they are not a one-to-one match, they complement each other. Table 1 lists the 10 basic principles of design thinking for results and how they relate to the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement.

No doubt further thought or input from others can contribute more relationship examples between the HPT standards (and practices) and these design-thinking principles. The point is, even a cursory comparison indicates a complementary and credible relationship. RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HPT PRINCIPLES AND PRINCIPLES OF DESIGN THINKING FOR RESULTS

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HPT PRINCIPLES AND PRINCIPLES OF DESIGN THINKING FOR RESULTS

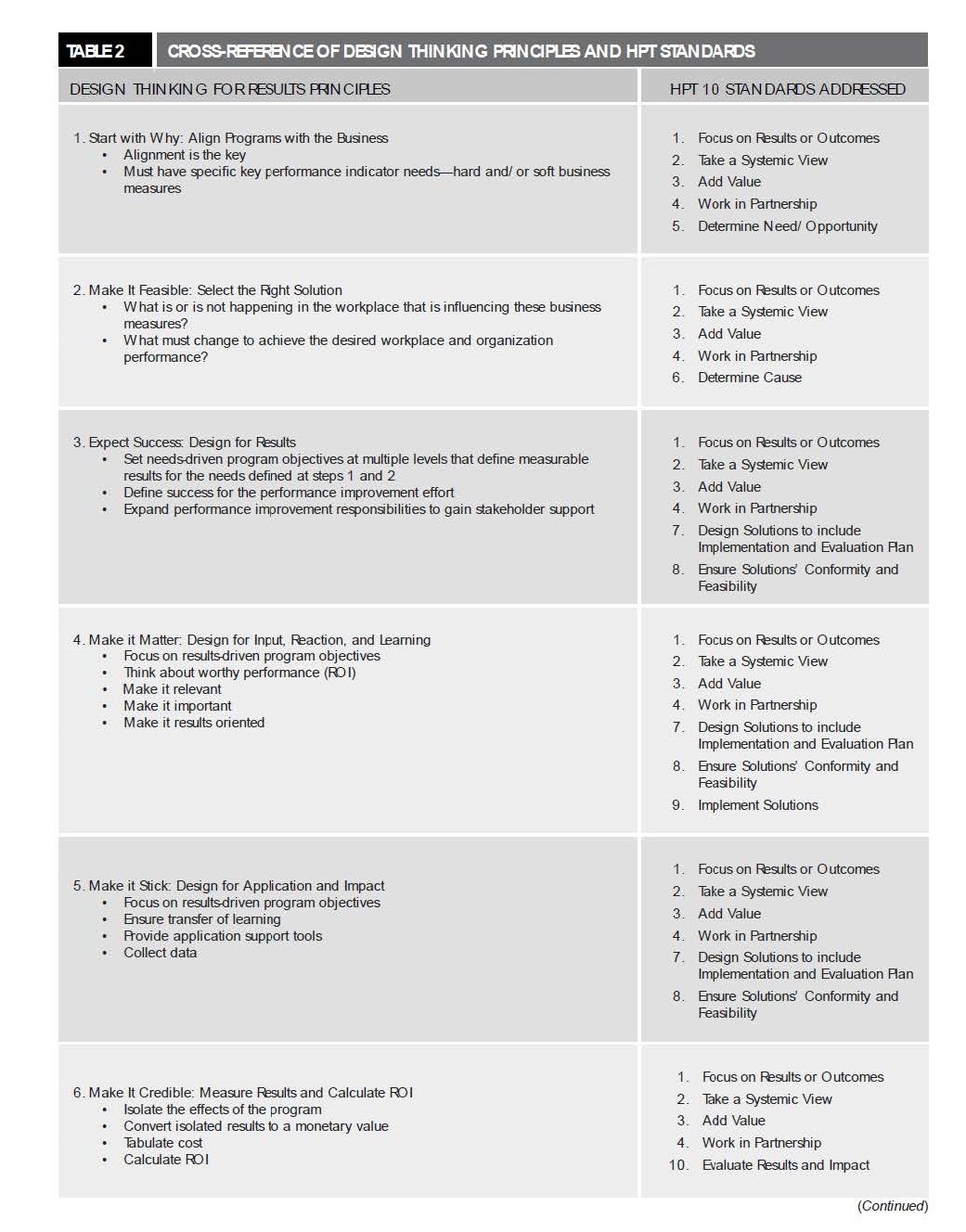

A critical element advocated by these 10 design-thinking principles is a systematic process model that provides a complementary framework for the HPT systematic process. Phillips and Phillips (2018) have crafted a systematic process model that seems to do this. This process model will also help address the understanding and application dilemmas now creating confusion about the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement mentioned at the beginning of this article. Table 2 lists this principles-driven design thinking process model, briefly describes each step and relates each process step to the applicable HPT standards. This design-thinking process begins with a principle learned from Sinek (2009), Pershing (2006), and ISPI’s 10 HPT standards to start with why, not start with.

This table demonstrates how these design-thinking-for-results principles help the HPT practitioner apply or plan to apply the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement.

A PRINCIPLE-BASED HPT LOGIC MODEL

A PRINCIPLE-BASED HPT LOGIC MODEL

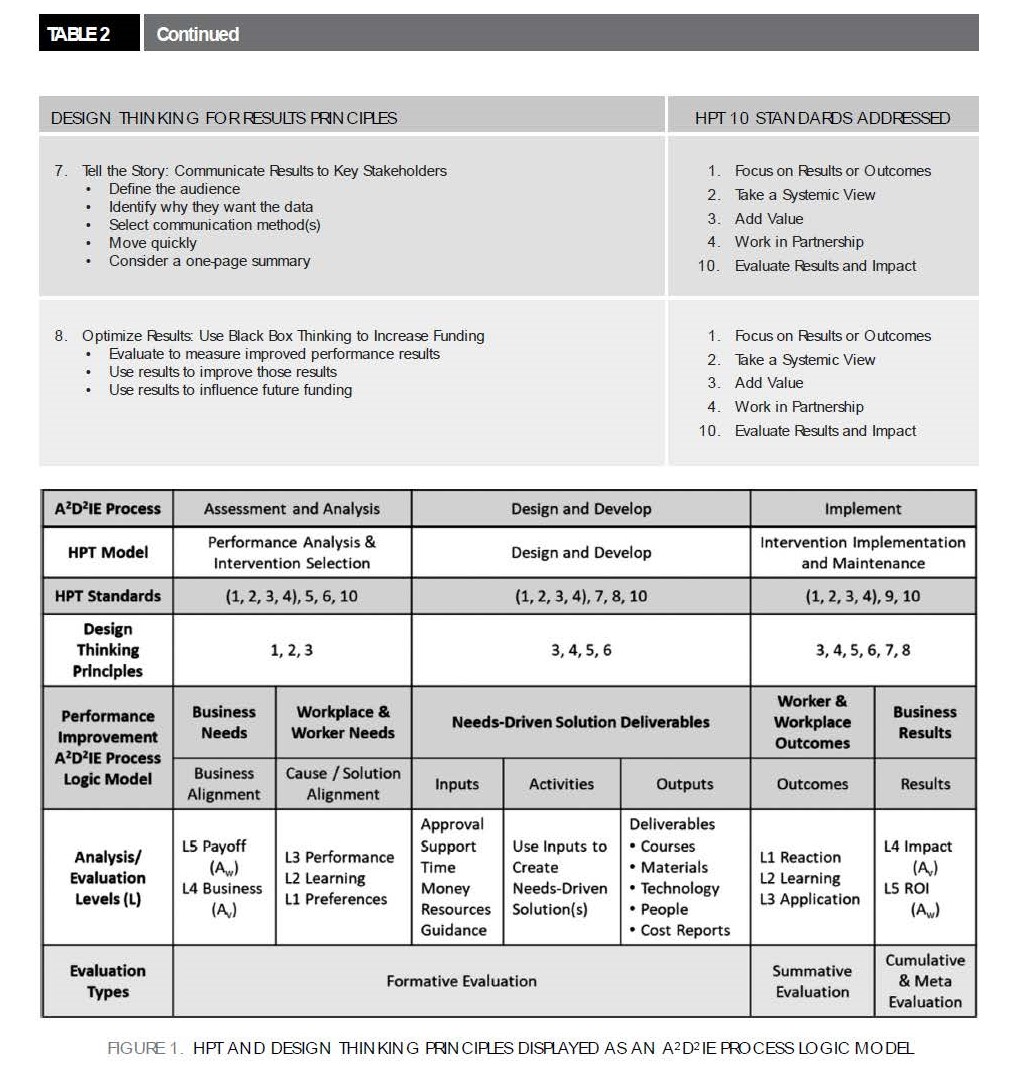

How does this new principle-based process help solve the Pershing Paradox? Fair question. Figure 1 helps answer this question. It represents a simple logic model (Kellogg Foundation, 2004) that integrates the six phases of the HPT model advocated by Van Tiem, Moseley, and Dessinger (2012), ISPI’s 10 performance improvement standards, the six phases of the A2D2IE process2, and the eight phases of the design-thinking process. The figure identifies the categories of data using the levels of evaluation that are familiar to performance improvement professionals (i.e., L1 = Level 1). The levels have different names associated with them during the analysis and evaluation phases, except in the case of learning.

These levels also help organize and align the logic model for the outcomes and results3 data categories at both ends of this logic model. This alone should help HPT practitioners distinguish between these two terms that are the fundamental focus of the first HPT standard. It also identifies where Worthy Performance (Aw) and Valued Performance (Av) occur. Finally, it distinguishes between the four types of evaluations advocated by the HPT model developed by Van Tiem, Moseley, & Dessinger (2012).

This may appear a bit confusing without taking some time to think it through. If the thought process begins with the ubiquitous A2D2IE process and the familiar HPT model (Van Tiem et al., 2012), these design-thinking principles can establish a step-by-step process the HPT practitioner can follow. While the HPT practitioner can use this integrated logic model framework to guide principles-based and standards-driven thinking, he or she probably would not show it to a customer or a client.

A SIMPLIFIED LOGIC MODEL TO PARTNER WITH CLIENTS AND CUSTOMERS

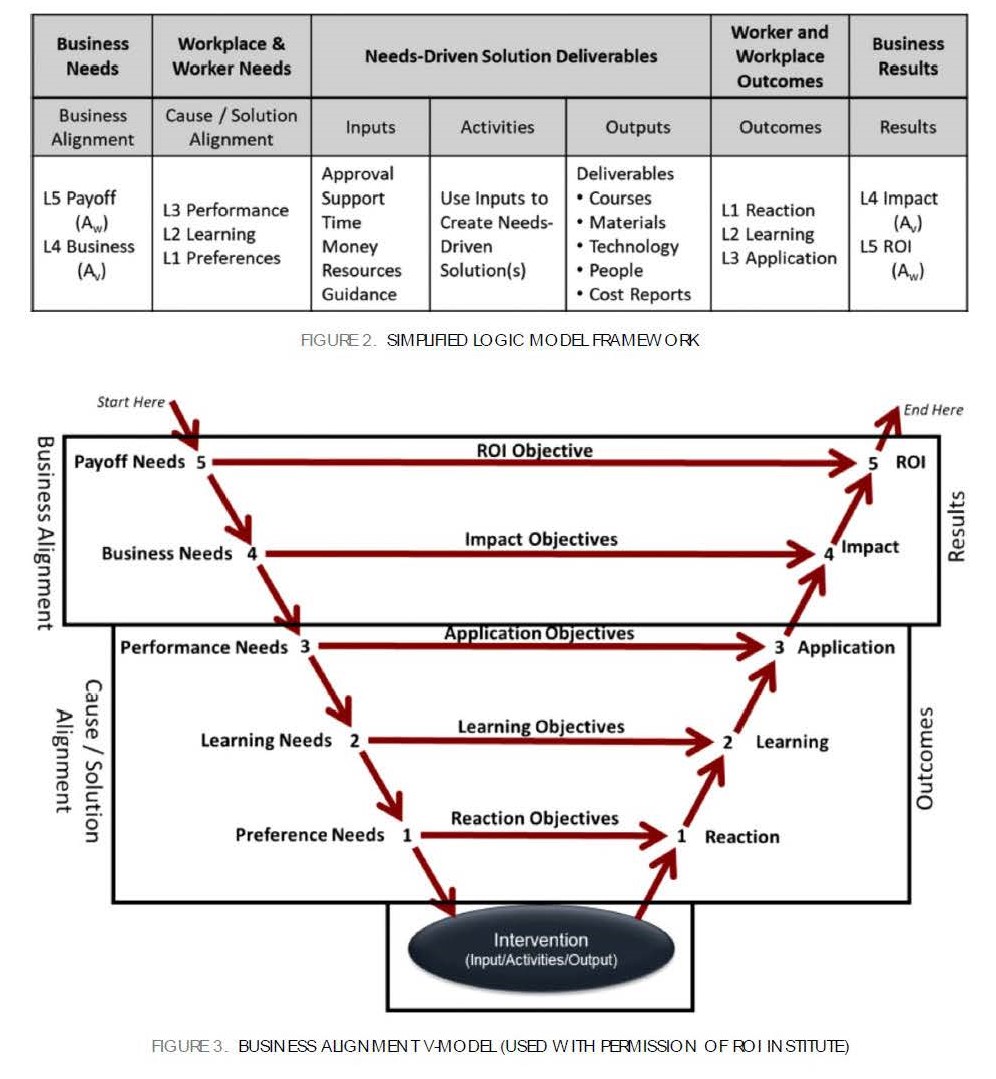

Figure 2 was developed from the more comprehensive logic model represented by Figure 1 to help HPT practitioners communicate and partner with their clients and stakeholders. This simple logic model likewise ensures that the HPT practitioner meets each of the 10 Standards of Performance Improvement.

HPT practitioners can apply Gilbert’s (1996) three- edge-ruler principles to communicate with their customers or clients.

While stakeholders may find this simple logic model more to their liking, another logic model has been developed by ROI Institute that translates this A2D2IE logic model into a more straightforward graphic that further applies Gilbert’s three-edged ruler principles.

THE BUSINESS ALIGNMENT V-MODEL LOGIC MODEL

The business alignment V-model visualizes an alignment between the five levels of needs and clearly distinguishes between the expected outcomes and expected results that the intervention is designed to address. The shape of the model does reflect the letter V. However, the “V” can easily represent the term “value” since that is what you are defining, measuring, and evaluating at each level. The added boxes show how the simplified A2D2IE logic-model process in Figure 2 overlays the business- alignment process model in Figure 3 and adds a new critical step often missing when the HPT standards are applied—needs-driven program objectives. These program objectives are a bridge that identifies what stakeholders at various levels of the organization value and expect to see after the program is implemented to declare it a success.

PROTECTING THE HPT PROFESSION’S NON-PRESCRIPTIVE PHILOSOPHY

What this business alignment V-model does not do is prescribe any A2D2IE–related models, theories, or practices. It accommodates any credible performance-consulting practices such as those developed by Hale (2007); Robinson, Robinson, Phillips, Phillips, and Handshaw (2015); and Swanson (2007), among others. Performance consulting should span all five need levels regardless of how the consulting models define or address them. For example, in today’s more socially conscious world, a level 5 (L5) pay- off and level 4 (L4) business needs can range from mega (societal) needs to micro (organizational) needs per the organizational elements model (Kaufman, 2000; Kaufman & Guerra-Lopez, 2013). By starting with the why question to align a program with the business, the HPT practitioner is heeding Drucker’s assertion that nothing is more useless than doing something efficiently that should not have been done in the first place. The business alignment V-model does this first.

Furthermore, this approach does not prescribe any cause analysis or instructional-design theories or models. At level 3 (L3) performance, the HPT practitioner can excel by using cause-analysis tools such as Gilbert’s (1996) behavior engineering model (1996), Rummler and Brache’s anatomy of performance or human performance system model (1995), along with other tools and practices such as Lean and Six Sigma. The HPT practitioner looks at the workplace to determine the root cause(s) of these underperforming level 4 business measures. This workplace-performance analysis includes the worker and the work4 itself as part of its systemic perspective and systematic approach (Addison et al., 2009). The HPT practitioner wants to learn what must change in the L3 workplace to improve the L4 business measures and achieve a positive L5 payoff. It is also during this third process step that HPT practitioners partner with the stakeholders to plan how to collect intervention-results data for levels 1 to 4 and analyze this data to determine the program’s effectiveness. The stakeholders want to know what they got in return for their money as that return relates to the needs-driven objectives that matter to them. These stakeholders will decide which level of evaluation will satisfy their expectations to declare the program, project, or initiative a success.5

In other words, for the appropriate performance improvement programs that influence business measures that matter to them, they want to know whether the improved performance (i.e., results) the HPT practitioner engineered was valuable and worthy. They may decide that outcome results are sufficient, depending on the program. Practitioners can even use a preferred evaluation methodology within this broader performance improvement framework such as Stufflebeam’s CIPP model (Guerra-Lopez, 2008), Brinkerhoff’s (2003) success-case method, Guerra-Lopez’s (2008) impact-evaluation process, or Thalheimer’s (2018) learning-transfer evaluation model.

In other words, for the appropriate performance improvement programs that influence business measures that matter to them, they want to know whether the improved performance (i.e., results) the HPT practitioner engineered was valuable and worthy. They may decide that outcome results are sufficient, depending on the program. Practitioners can even use a preferred evaluation methodology within this broader performance improvement framework such as Stufflebeam’s CIPP model (Guerra-Lopez, 2008), Brinkerhoff’s (2003) success-case method, Guerra-Lopez’s (2008) impact-evaluation process, or Thalheimer’s (2018) learning-transfer evaluation model.

CONCLUSION

This advanced logic model may look good on paper. What is missing is evidence that it works. Part three of this three-part series will provide a case study that shows how what was covered in the first two parts provides a framework that works in practice. It will connect all the dots and bring clarity to what has been covered this far.

ENDNOTES

1 Given Gilbert’s (1996) desire to use the term accomplishment, this article classifies the results of the first ISPI principle to mean valued and worthy accomplishments. The outcomes included in this first principle are considered a means to an accomplishment.

2 A2D2DIE = assess (determine needs), analyze (determine causes), design, develop, implement, evaluate. Guerra-Lopez (2008) coined A2DDIE to add “assess” to the ADDIE process. Why not create consistency with the first two letters that repeat to make it A2D2IE? That is what I will do in this article.

3 For this article, outputs represent immediate results of activities such as solution deliverables. Outcomes represent short-term and intermediate results of the implemented solution(s). Outcomes are a means to an end (i.e., accomplishments). Results represent long-term and ultimate accomplishments of the implemented solution(s).

4 I prefer Crosby’s (1980) definition of work that “all work is a process” because it provides a systemic perspective.

5 Global benchmarking studies conducted by ROI Institute (Phillips & Philips, 2018) indicate executives use eight criteria to decide when to evaluate to the return in investment (ROI) and impact levels. Four are linkage to strategic objectives, cost, importance of the program, and linkage to problems and opportunities. In addition, it is not appropriate to evaluate every program to the impact or ROI levels. For example, it is difficult to justify the expense to evaluate compliance courses, technical training, or short one-day programs beyond the learning or maybe application levels. The costs to evaluate to the higher levels would most likely exceed the monetized benefits gained.

Therefore, ROI Institute recommends the following evaluation targets for each level: reaction and planned Action: 90–100%; learning: 60–90%; application and implementation: 30–40%; impact: 10–20%; and ROI: 5– 10%. Gilbert (1996) also made this point when he wrote, “It is frequently useful to quantify measures of accomplishment, and these measures should have economic correlatives” (p. 24). Gilbert goes on to write that we should focus on the ones that someone says have value because it matters.

References

Addison, R., Haig, C., & Kearney, L. (2009). Performance architecture: The art and science of improving organizations. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Brinkerhoff, R.O. (2003). The success case method: Find out quickly what’s working and what’s not. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.Crosby, P.B. (1980). Quality is free: The art of making quality certain. New York, NY: Mentor.

Crosby, P.B. (1980). Quality is free: The art of making quality certain. New York, NY: Mentor.

Esque, T.J. (1996). Forward. In T.F. Gilbert (Ed.), Human competence: Engineering worthy performance (Tribute ed.). Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement.

Gilbert, T.F. (1996). Human competence: Engineering worthy performance (Tribute ed.). Silver Spring, MD: International Society for Performance Improvement.

Guerra-Lopez, I.J. (2008). Performance evaluation: Proven approaches for improving program and organizational performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hale, J. (2007). The performance consultant’s fieldbook: Tools and techniques for improving organizations and people (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Kaufman, R. (2000). Mega planning: Practical tools for organizational success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kaufman, R., & Guerra-Lopez, I. (2013). Needs assessment for organizational success. Alexandria, VA: American Society for Training and Development.

Kellogg Foundation. (2004). W.K. Kellogg Foundation logic model development guide. Retrieved from https://www.wkkf. org/resource-directory/resource/2006/02/wk-kelloggfoundatio n-logic-model-development-guide

Pershing, J.A. (2006). Human performance technology fundamentals. In J.A. Pershing (Ed.), Handbook of human performance technology: Principles, practices, potential (3rd ed.) (pp. 5–34). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Phillips, J.J., & Philips, P.P. (2018). The value of innovation: Knowing, proving, and showing the value of innovation and creativity. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Robinson, D.G., Robinson, J.C., Phillips, J.J., Phillips, P.P., & Handshaw, D. (2015). Performance consulting: A strategic process to improve, measure, and sustain organizational results (3rd ed.). Oakland, CA: Barrett-Kohler.

Rummler, G.A., & Brache, A.P. (1995). Improving performance: How to manage the white space on the organizational chart. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. New York, NY: Penguin Group

Swanson, R.A. (2007). Analysis for improving performance: Tools for diagnosing organizations and documenting workplace expertise (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Barrett- Koehler.

Thalheimer, W. (2018). The learning-transfer evaluation model: Sending messages to enable learning effectiveness. Retrieved from https://www.worklearning.com/wp-content/ uploads/2018/02/Thalheimer-The-Learning-Transfer-Evaluatio n-Model-Report-for-LTEM-v11.pdf

Van Tiem, D.M., Moseley, J.L., & Dessinger, J.C. (2012). Fundamentals of performance improvement: Optimizing results through people, process, and organizations (3rd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Winter, B. (2018). Why Gilbert matters. Performance Improvement, 57(10), 6–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21809

About the Author

TIMOTHY R. BROCK, CPT, PhD, CRP, is the director of consulting services for ROI Institute, Inc., the leading source of ROI competency building, implementation support, networking, and research. He helps organizations implement the ROI Methodology at more than 6,000 organizations in over 60 countries. He serves on the results-based management faculty at the United Nations System Staff College (Turin, Italy) and the Training and Performance improvement faculty at Capella University (Minneapolis, Minnesota). He earned his PhD in Education from Capella University with a specialization in Training and Performance Improvement. His latest journal article, “ Performance Analytics: The Missing Big Data Link Between Learning Analytics and Business Analytics,” appeared in the August 2017 (Volume 56, Issue 7) Performance Improvement journal published by the International Society for Performance Improvement (ISPI). He may be reached at Tim@roiinstitute.net.