Your cart is currently empty!

The Challenge Facing Healthcare Improvement Projects

Healthcare is experiencing radical change. A significant and growing portion of the gross domestic product (GDP) in the United States and other countries is devoted to healthcare. Payment methods are shifting from fee for service (utilization) to pay-for-performance. Budgets are constrained, reduced, and under significant scrutiny more than ever. Healthcare executives are increasingly making hard decisions about budgets. They need evidence that program investments are adding value and improving outcomes. For example:

- Chaplains in hospital settings are being asked to show the value they deliver to healthcare organizations, facing a reduction in numbers if they do not.

- A large health system has challenged a Healthy Living group to show the impact and value of their programs.

- Public health professionals are being asked if increasing efforts and associated costs to include more individuals in cancer screening are producing results.

- A program to increase managerial competency is being required to show a payoff through improved staffing.

These executives are implementing healthcare improvement projects to improve patient quality, reduce healthcare costs, provide more access, and increase patient satisfaction. They need to know if these programs are successful.

Responding to the Challenge

The healthcare industry needs a systematic approach that uses a proven measurement process to generate credible evidence of the impact of investments on outcomes (or lack thereof). The ROI Methodology® developed by ROI Institute is the most-used planning and evaluation system in the world. With almost 100 books to support this methodology, ROI Institute has demonstrated that this methodology delivers evidence in terms executives understand, appreciate, and support, while also meeting financial officer approval. This approach has gained the attention of governments with the federal governments of 26 countries adopting the ROI Methodology. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have also seen value in this approach, such the United Nations which started using this method after the passage of a UN General Assembly resolution in 2008. Nonprofits are also using it, including charities, foundations, associations, and religious organizations. Approximately 300 healthcare organizations are now using the process, sparked in part by the book Measuring ROI in Healthcare (McGraw-Hill, 2015).

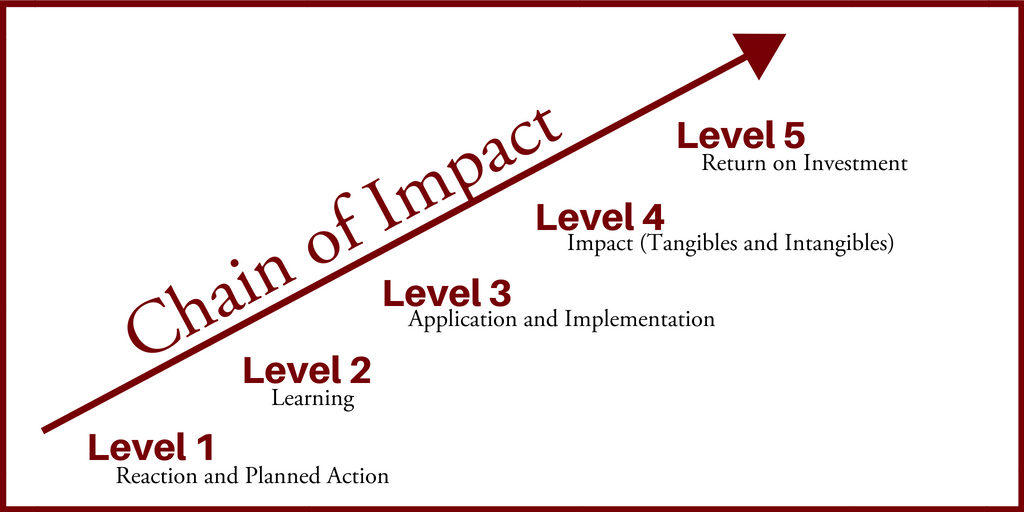

- Reaction & Planned Action: These data measure participant satisfaction with the program/planned action and ascertains if participants are engaged, supportive, and committed. For example, team members are committed to a quality improvement project to improve wait times for a clinic appointment and feel that this is a worthwhile effort, a good use of their talent, and will likely lead to improvement that will benefit the clinic staff and their patients.

- Learning: These data illustrate that program participants know what to do and how to accomplish their mission. For example, team members are competent in improvement science methods, they are knowledgeable about small tests of change, and they know how to track progress in a run chart.

- Application & Implementation: This step documents that specific actions have been taken to make the program successful. For example, the team is implementing changes, tracking progress, identifying what works and sustaining success.

- Impact: This level shows the extent to which outcome measures have been affected. Two types of data are important. First, tangible measures can be monetary values, such as revenue earned or costs avoided. Tangible measures may also be measures that can be converted to monetary values, such as the time of personnel. Second, intangible measures are important outcomes (such as patient satisfaction or quality of life) but are not converted to a monetary value.

- ROI: Measurement at Level 5 answers one critical question: how do the costs of an intervention compare to the benefits the intervention was designed to improve?

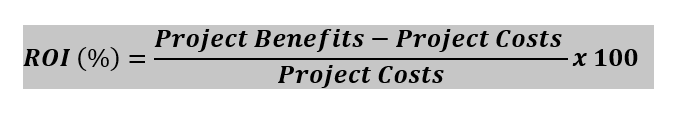

The return on investment is calculated by dividing the net monetary benefits by project costs. The net monetary benefits are calculated as the project monetary benefits minus the project costs. In formula form, the ROI becomes:

Special Points about Impact and ROI:

Our Philosophy and Principles of Practice

Isolate the effect of the program on outcomes: A credible method must ascertain whether and to what extent an improvement was the result of the program designed to cause those changes. Multiple experimental and analytical methods exist to isolate the contribution of programs to outcomes. While the ROI Methodology® uses these methods, they are simply not practical in some situations. To respond to these limitations, ROI Institute pioneered the use of stakeholder estimates as a practical and credible method of isolating the portion of impact due to the program implementation (an example below illustrates this method).

Conservative assumptions: Many assumptions are made during the collection and analysis of data. These assumptions need to be conservative as it is better to understate and communicate believable results to increase the likelihood of accuracy and buy in. In reporting ROI, this plays out in two ways:

- First, the costs are fully loaded; the conservative approach is to include all costs related to a program so that the total cost is not understated. In the formula, fully loading the cost has the effect of dampening a positive ROI, as well as making a positive ROI result more believable.

- Second, extreme values and unsupported claims of impact are not used. Substantiated estimates of impact are also moderated under the assumption that some, but not all, benefits are the result of the program. Conservatively estimating benefits has the effect of dampening a positive ROI and making a positive ROI result more believable.

Hospitals are complex organizations that serve a diverse patient population. In treating a variety of patients, medical professionals must have specialized supplies available when needed. The purchase of too few of any item, and there is a risk that the product is not available when needed; purchase too many, the risk is inflating budgets to purchase and store materials. Purchasing supplies in such an environment is a complex and high-volume activity and thus was a focus of an improvement in the process. A tangible measure of value was needed to determine if efforts to improve processes were effective and worth the cost.

Participants in the program attended an educational workshop to become familiar with the changes in the procurement processes and to learn how to use a software system that supported the process. Stakeholders wanted to know if the intervention to improve processes was effective and, if so, if there was a financial benefit. The financial benefit could signal if further investment was prudent. An evaluation of the intervention included the five levels of evaluation and all six types of data.

Data collected indicated that the process change and education workshop were well received (reaction data, level 1) and that participants understood the process and how to implement it with the new software platform (learning data, level 2). Application data (level 3) showed that, for a variety of reasons, the new process was implemented but not 100 percent of the time and, in some situations, staff reverted to an older, slower process.

The tangible measure of impact (level 4) was time saved because of the new process. If individuals who worked more efficiently with the new process found that increasing volume of processing would not require additional staff, then the time saved was converted to a monetary value based on a staff person’s hourly compensation; this was the tangible/monetary measure. The financial benefit was calculated as time saved per transaction multiplied by the total hourly compensation (salary and benefits), and it applied only to those transactions for which the new process was implemented.

In addition to the monetary benefits, several nonmonetary benefits were identified. These included increased reduced risk of out–of-stock supplies. Intangible measures of impact (level 4) could potentially have been monetized as well, but the link to monetary benefits was less obvious to stakeholders than the value of personnel time. As such, a conservative approach that had validity for stakeholders focused on these measures as intangible nonmonetary benefits.

An educational session was delivered as an intervention to facilitate the adoption of the new procedure by staff. Two steps were taken to determine the ROI (level 5) of this intervention: 1) calculate the fully loaded cost of the educational program (e.g. cost of time of participants and faculty, materials, space); 2) determine if time savings for procurement could be attributed to the educational intervention by isolating the effect of the workshop of changes in procurement and then calculate the Return on Investment (ROI).

Isolating the contribution of the educational intervention to the financial outcome relied on probabilistic judgments from stakeholders. Stakeholders were asked to consider the multiple factors that could be responsible for the financial benefits, and then estimate the extent to which training may have responsible for the benefits. Estimates could range from zero percent (which was equivalent to attributing no impact) to 100 percent (which was equivalent to training being the sole reason for impact).

Next, these same stakeholders estimated their confidence in this attribution, with zero percent being no confidence and 100 percent being complete confidence. Estimates of impact are seldom at 100 percent, and among a group of stakeholders the average impact is generally less than 100 percent. Likewise, an individual stakeholder’s confidence in their estimate is seldom at 100 percent. Multiplying the two values provides a conservative estimate of impact because the confidence estimate has the effect of lowering the estimate of impact.

On average, the estimate of impact attributed to the intervention was 25 percent. The estimate of the confidence in this attribution was 85 percent. In other words, stakeholders indicated that 25 percent of any benefit could be isolated and attributed to the educational intervention and felt 85 percent confident in that estimate. The calculated monetary benefit was $125,000, the isolated benefit attributed to the workshop was $25,562 (.25 multiplied by .85, multiplied again by 125,000). The calculated cost of the education program is $10,000, and the net benefit (benefit less cost) was $16,562; dividing this value by the cost of resulted in an ROI of 166 percent. In other words, for every dollar invested in training, the process improvement yielded a dollar payback, plus an additional $0.66.

- is a credible process that shows the contribution of important programs and is used to improve programs, gain support for the programs, build relationships with key executives and administrators, and secure funding for programs in the future.

- is a flexible, versatile process that can withstand the scrutiny of critics and provide the CEO and CFO with credible data.

- has achieved and sustained the position as the leading approach to valuing investments in improvement programs by:

- reporting a balanced set of measures;

- implementing a methodical, step-by-step process; and

- adhering to standards and philosophy of maintaining a conservative approach and credible outcomes.

- has proven useful in multiple industries – including healthcare – and is well-suited to the challenges of healthcare.

ROI Institute offers a variety of services including: consulting, workshops, ROI Certification, publications, and speaking services to hospital chains, healthcare systems, clinics, pharmaceutical organizations, and various healthcare groups. Dr. Dan McLinden, Ed.D., has joined ROI Institute to take the lead for this practice with the help of the ROI Institute team and using our book, Measuring ROI in Healthcare, as the basis of this practice.

“Dan has one of the most impressive backgrounds to tackle this important challenge,” explained Jack J. Phillips, chairman of ROI Institute. “He has thirteen years of consulting experience with Accenture, twelve years of healthcare experience with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, faculty experience as an associate professor at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and experience working with ROI Institute for several years on previous assignments. He has been a Certified ROI Professional for almost two decades and will bring a wealth of experience and knowledge to individuals and organizations in this important field.”

“We’ve known Dan for almost twenty years, and we are proud to have him taking a leadership role with this important segment of our market,” added Patti Phillips, president and CEO of ROI Institute. “Dan is an excellent consultant, effective facilitator, very thoughtful presenter, prolific writer, and outstanding researcher. We are glad to have him driving this much needed effort in the field of healthcare.”

Daniel McLinden, Ed.D.

Dan McLinden, Ed.D., is an associate of ROI Institute with a specialization in healthcare. Most recently, he was a senior director in the division of medical operations at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC) and an associate professor in the College of Medicine at the University of Cincinnati. Prior to joining CCHMC, Dan was a consultant specializing in healthcare. Some of his past clients include the National Institutes for Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the American Cancer Society.

Dan has more than 25 years of experience in program evaluation, particularly in the evaluation of investments in human capital. He has led evaluation efforts at CCHMC and Accenture, as well as consulting for multiple corporate and government organizations. Additionally, he is well-versed in Improvement Science applied to healthcare. He attended the Improvement Science program at CCHMC’s Anderson Center for Health Systems Excellence and has led and participated in multiple quality improvement projects.

Dan enjoys speaking and writing. His work has been published more than 30 times in peer-reviewed journals, he has made more than 50 presentations at national and international conferences, and he has contributed to seven different books. Dan has been either a principal investigator or key investigator on multiple research grants and contracts in healthcare.

In his personal life, Dan enjoys spending time with his wife, children, and grandchildren. He also enjoys riding his motorcycle when the weather is nice and tries hard to play his classical guitar.